Defeating fascism in the UK and Europe

Tonight on Revolutions Per Minute, we travel to the United Kingdom, where far-right riots have swept the country. We ask Alex Roberts, a UK-based organizer and host of the anti-fascist podcast 12 Rules for WHAT, how communities can fight back. We also speak to Paolo Gerbaudo, a senior research fellow at Complutense University in Madrid, on the role of social media in contemporary politics.

The Intersection of Reproductive and Trans Rights: A Call for Bodily Autonomy

By Rose L, aka Rosenriot

Let it be known, I did everything I was supposed to do.

2017 was a different time. I still thought I was cis. I did not want children. I knew I wasn’t fit to be a mother. I have health conditions that I didn’t ever want passed down. I was abstinent at the time, but had been previously sexually assaulted. I knew getting pregnant wasn’t going to always be my decision.

So I did the responsible thing and I pursued sterilization. I went to my OBGYN, who had cared for me for the prior 10 years. The nurse came in to see me, and asked me about the nature of my visit. I told her I wanted sterilization. I’d done my research. I was sure. The nurse smiled and said, “I can’t imagine that being an issue. The doctor is a huge feminist.” I was so relieved.

The doctor came in. She sat down and proceeded to lecture me on what a disastrous procedure I was considering. What if I changed my mind? What would my future husband think? What if my inability to bear a child affected my desirability?

I was crushed. But I persisted. There were other doctors. I was eventually able to find a doctor willing to perform a sterilization on me. A male doctor, in fact, who only asked me three questions: Was I sound of body? Yes. Was I sound of mind? Debatable but yes. And did I want this? Absolutely, yes. A month later, I received a tubal ligation and uterine ablation, the latter being a doctor recommendation to ease my period, as I would no longer have use for a menstrual cycle.

But again, 2017 was a different time. Republicans had not yet started proposing total abortion bans. So when my doctor warned me that I would have an increased risk of ectopic pregnancy from my procedure, I didn't even blink an eye. I was so naive then.

Since getting my procedure, 14 states have passed total abortion bans. These bans not only criminalize abortions, they often conflate ectopic pregnancies with viable fetuses. The truth is that ectopic pregnancy by definition is not viable, as the fertilized egg plants itself outside of the womb. Ectopic is also medically and factually an abortion.

Lately Republicans have tried to redefine abortion to not include cases of rape, incest, and life-threatening medical conditions such as ectopic pregnancies. When being questioned by Rep. Ayanna Pressley about ectopic pregnancies, Erin Hawley, senior counsel for Alliance Defending Freedom, a known hate-group according to the Southern Poverty Law Center, used such rhetoric: “That’s not an abortion because it does not have the intent to end the life of the child.” This misunderstands abortion: abortion is not subject to intent. It is objectively a medical procedure, and a safe one at that.

Abortion bans often prohibit doctors from prescribing methotrexate in the early stages of an ectopic pregnancy to abort the unviable egg and to save the pregnant person. Without early intervention, an ectopic pregnancy can result in hemorrhage, sepsis, or organ failure. These can only be prevented by abortive surgery, a surgery doctors are now terrified to perform for fear it will violate their state’s abortion laws. These laws put doctors in the position of going to prison for saving a pregnant person’s life. It puts the pregnant person in the position of dying, waiting on the operating table for help that will never come.

I did everything right in 2017, but Republicans would still have me and others like me dead. They’ve consistently moved the goalposts of what is acceptable behavior for people with uteruses, pushing it farther and farther to outlaw exceptions for ectopic pregnancy, to outlaw exceptions for incest, to outlaw exceptions for rape, to outlaw contraception, to make sure that everyone with a uterus slowly but surely loses their bodily autonomy.

But Republicans didn’t stop there. When I came out as trans and nonbinary in 2019, I was still in the state of Tennessee. There were only a handful of doctors willing to prescribe Hormone Replacement Therapy, or HRT, a treatment I wished to pursue in my transition. At least when I found a doctor for my sterilization, I only had to wait a month. For HRT, the waitlists for these doctors were years long, with spots only opening up as trans patients moved away or passed away, either of old age or by their own hand. And many did pass away by their own hand, as increasingly oppressive laws around trans people passed left and right without any consideration for their quality of life or existence.

And that’s what this is all about, isn’t it? Our right to exist, autonomous, as we are, as we choose to be.

I hear controversy in the pro-choice movement about using terms like “pregnant people” or “people with uteruses” and whether trans people deserve to be included or considered the same way as cis women are in this struggle. But the fact of the matter is, when we’re in the hospital, and I’m bleeding out from an ectopic pregnancy, and you’re giving birth to a child you were forced to have because there were no abortion clinics in your area, it’s not going to matter that you’re cis and I’m trans; that you’re a woman, and I’m not. It’s going to matter that we had wombs and we tried to use them in ways that were unacceptable to the heteronormative cisnormative patriarchal establishment.

Trans or cis, our bodily autonomies are intertwined. Our right to exist unyielding is intertwined. It might be easy for you, if you are a cishet ally, to think that the shooting at Club Q doesn’t affect you. That bills like SB49 aka the “Don’t Say Gay” bill have nothing to do with you. That drag shows being protested by Proud Boys are a problem, but not your problem. But my people, queer and trans people, are canaries in the coal mine. If you think violence against abortion clinics and feminist spaces won’t increase too, if you think violence in general will not increase, you haven’t been paying attention. Any deviation from the path that Conservative Evangelical fascists would prescribe to you will be met with extreme violence.

In just the last few months I have watched my fellow drag performers, of all genders, be targeted by hate groups. I myself was targeted by Libs of TikTok for a drag brunch I wasn’t even in, a drag brunch that Proud Boys showed up to, heavily armed, threatening my fellow performers. I watched a livestream of Proud Boys protesting Naomi Dix in Moore County, before shooting up a power station and cutting electricity to an entire population for days on end. After Club Q, I attended the Trans Day of Remembrance Vigil in Raleigh and spoke the name “Daniel Davis Aston”, a bartender at Club Q, before major news outlets had even grabbed hold of his name. I learned he was one of the victims through a drag performer I knew from Colorado Springs. That drag performer said when he moved to Colorado Springs, Daniel was the first friend he made there, and Daniel even helped him obtain top surgery. Daniel’s mother said his death is “a nightmare that you can't wake up from.”

We are about to be in that neverending nightmare, too. Violence will increase against all marginalized peoples. No longer is this a fight for women’s rights or trans rights. In fact, our greatest mistake was ever thinking these fights were separate. The struggles of all those marginalized and targeted by Conservatives and Christo-Fascism are united. They will not stop until trans and queer people are dead or conforming, they will not stop until women are dead or conforming, they will not stop until Black people are dead or conforming, they will not stop.

So it’s time for us to begin. It’s time for us to embrace the intersectional approach they know will defeat them, that they try everything to dissuade. If we continue to fight this fight separately, we will not survive.

NC Triangle DSA has several ways to get involved with the intersectional fight facing us. The Socialist Feminist Working Group is making headway on shutting down a local Crisis Pregnancy Center, aka Anti-Abortion Center, via pickets and escalations. The Queer and Trans Solidarity Working Group is focusing on building mutual aid support networks for Queer folk in the Triangle to rely on whether the federal or state governments are blue or red or fallen. These, and several other Working Groups, fall under our chapter’s Priority Campaign, a resolution voted on by our chapter to increase our focus on bodily autonomy issues.

We must unite. We must realize that many of us here are both oppressed and oppressor, and to unlearn the systems of supremacy that make us perpetuate harm into our communities. We must learn how to protect ourselves, to heal ourselves, to create the skills that help us cultivate safety.

The time for awareness is over. The time for action is now.

About the Author:

Rose L (they/them), also known by their drag persona ROSENRIOT, is a member of NCTDSA, activist, and queer performer living and working in Central NC. They’ve lived in the South for over half their life, and can be found working on sewing and craft projects in places you wouldn’t expect sewing or crafting to occur.

NPEC Accepting Applications for Vacancies till August 15th

We have a few vacancies on NPEC right now and so are opening up applications on an expedited basis until August 15.

Thank you for your interest in joining DSA’s National Political Education Committee! We’re excited to have you help develop our national political education program.

We’re taking applications through August 15th, 2024 . Applications are reviewed by NPEC’s Steering Committee and appointed by the NPC. These applications will be for the remainder of this current term is May 1, 2024 – April 30, 2025. Applicants will be notified of acceptance via e-mail by the end of August.

If you have any questions or concerns, feel free to reach out to the Political Education Committee at politicaleducation@dsacommittees.org

Robinson Campaign Takes a Page Out of the Anti-Abortion Playbook in New Ad

by Saige Smith

Robinson recently released a new ad appearing to take a more moderate stance on abortion. His stance on abortion hasn’t changed; he’s only fine tuned his talking points in the wake of the upcoming election.

WATCH NOW: Mark Robinson’s new campaign ad:#ncpol #ncgov pic.twitter.com/TgLurZnpLQ

— Mark Robinson (@markrobinsonNC) August 2, 2024

Mark Robinson has been vocal about his extreme anti-abortion beliefs for years. He previously said “Abortion in this country is not about protecting the lives of mothers. It’s about killing the child because you weren’t responsible enough to keep your skirt down” and “If I had all the power right now, let’s say I was the governor and I had a willing legislature, we could pass a bill saying you can’t have an abortion in North Carolina for any reason,” yet in the ad he pivots to supporting “commonsense” legislation with “exceptions.”

This ad is a perfect encapsulation of the GOP’s post-Dobbs rhetorical strategy. This article is going to detail how and why this is just the latest attempt by the anti-abortion movement to save face now that the harsh reality of abortion bans has really come to light post-Dobbs. The anti-abortion movement thrives off of abortion stigmatization, medical misinformation, and emotionally charged rhetoric, and this 30 second ad is full of it.

Fueling abortion stigma

“30 years ago, my wife and I made a very difficult decision – we had an abortion. It was like this solid pain between us that we never spoke of”. Then his wife, Yolanda Robinson, states “it’s something that stays with you forever”. Mark Robinson continues, “that’s why I stand by our current law. It provides commonsense exceptions for the life of the mother, incest, and rape … Which gives help to mothers and stops cruel late-term abortions. When I’m Governor, mothers in need will be supported”

While neither Robinson went into detail about Yolanda’s abortion during the short ad, it’s important to note a few things. Research shows that people experience a mix of positive and negative emotions in the days after having an abortion, with relief predominating. The intensity of all emotions diminishes over time, mostly over the first year. The vast majority – 95% – of people who get abortions said that it was the right decision for them. People who are denied abortions have worse physical and mental health and worse economic outcomes than those who seek and receive abortions.

Mark starts by contributing to the idea that abortion itself is a difficult decision. Abortion is sometimes difficult and sometimes not – there are many nuances around having an abortion. Every decision to have an abortion is unique, individual, and deserving of respect. Just like they were able to decide to have an abortion 30 years ago, all people should be trusted to make the reproductive healthcare decisions that are best for them — including abortion — on their timeline and with the resources they need.

The beginning of the ad further implies that abortion is something regretful and shameful and therefore the wrong decision to make. Abortion stigma is perpetuated by abortion restrictions and inevitably leads to criminalization even when there are no authorizing statutes. Abortion stigma is everywhere, whether it’s the protesters at the clinic harassing you on your way in for your appointment, your parents threatening to kick you out, a teacher you confide in who tells you that’s not something you should talk about, a toxic romantic partner pressuring you against what you want for your pregnancy, the societal pressure to become a mother while ostracizing child-free people, or the laws creating barriers to abortion care.

The anti-abortion movement’s post-Dobbs rhetorical pivot

More and more horror stories have emerged since the overturn of Roe v Wade of people being forced to carry doomed pregnancies, give birth in a car after being turned away from the emergency room, or forced to travel out of state for abortion care – and the anti-abortion movement knows this.

Post-Dobbs, Republicans have had to deal with how unpopular and harmful their abortion bans are. Rather than admitting that pregnancy is too complex to legislate and addressing how these bans are detrimental to pregnant people, the anti-abortion movement is focusing on fine-tuning their talking points: by focusing on exceptions in abortion bans that do not work; moving away from calling abortion bans “bans” and instead calling abortion bans “commonsense consensus” or “compromise”; and performative amendments that do nothing but attempt to repair their image.

By design, exceptions do NOT work

On paper, abortion bans may include exceptions, but in reality, these exceptions are nothing more than PR points for the anti-abortion politicians who pass these nightmare bans. These supposed “exceptions” are intentionally vague and narrowly defined so that it’s impractical to actually use them — and that’s the point. When Republicans fall back on how the current ban has “commonsense exceptions for the life of the mother, incest, and rape”, this is a rhetorical strategy to defer the actual problem — the wide-ranging harm caused by banning abortion — and pivot to appealing to the less stigmatized reasons people get abortions.

In North Carolina, abortion is banned after 12 weeks with a few vague exceptions up to 20 weeks. For example, North Carolina’s exception for the life of the mother defines a medical emergency as the following (emphasis mine):

“Medical emergency. – A condition which, in reasonable medical judgment, so complicates the medical condition of the pregnant woman as to necessitate the immediate abortion of her pregnancy to avert her death or for which a delay will create serious risk of substantial and irreversible physical impairment of a major bodily function, not including any psychological or emotional conditions. For purposes of this definition, no condition shall be deemed a medical emergency if based on a claim or diagnosis that the woman will engage in conduct which would result in her death or in substantial and irreversible physical impairment of a major bodily function”.

The language used does not define what exactly constitutes a “major bodily function,” nor what constitutes a “substantial and irreversible physical impairment” to a major bodily function. This intentionally vague language puts physicians in a bind when pregnant patients need an abortion for health reasons. It shifts the decision away from the medical providers and patients and over to the facility’s lawyers. The second part of this definition shows how Republicans anticipate that abortion bans will make people suicidal, so they specifically outline that abortions are not allowed to preserve psychological or emotional well-being of the mother.

How much of an “exception” is it if people have to wait for their vital signs to crash before they’re legally allowed treatment? How much permanent harm to one’s organs is an acceptable trade-off? Exactly how close to death does one have to get to so they can receive treatment?

As Jessica Valenti pointed out, “This is all by design; Republicans deliberately write in exceptions that will be near-impossible to use. So why in the world aren’t Democrats shouting as much from the rooftops? Instead, they’re giving Republicans a tremendous gift: The ability to point to exceptions that no one can actually use as proof that they’re ‘softening’ on abortion … If the exceptions meant to save people’s lives aren’t usable, what makes anyone think those for rape and incest would be?”

Reporting requirements and time limits place barriers in the way of survivors of sexual assault seeking abortion care in states with abortion bans. When you add in a culture that doesn’t believe victims about sexual violence, the purpose and ineffectiveness of rape and incest exceptions become more evident. When the state forces victims to provide proof of their assault to receive healthcare, the state inevitably creates policy that protects sexual abusers. This is the side that wants you to think that they’re the moderate ones.

Compromise? Who? Common sense? Where?

“30 years ago, my wife and I made a very difficult decision – we had an abortion. It was like this solid pain between us that we never spoke of”. Then his wife, Yolanda Robinson, states “it’s something that stays with you forever”. Mark Robinson continues, “That’s why I stand by our current law. It provides commonsense exceptions for the life of the mother, incest, and rape which gives help to mothers and stops cruel late-term abortions. When I’m Governor, mothers in need will be supported”

Calling North Carolina’s 12 week abortion ban “common sense” and intentionally not calling it a ban are tactics we saw sprout up last year when the NC Senate was hearing debate over S.B.20. As Jessica Valenti pointed out, “Bill sponsor Sen. Joyce Krawiec says, ‘this is a pro-life plan, not an abortion ban.’ (Let that sink for a moment: Republicans are so afraid of abortion rights’ popularity, they’re not even willing to call their bans ‘bans’ anymore.)”. Mandating humiliating, burdensome, and time sensitive barriers to healthcare is far from “common sense”. Going directly against medical providers warnings about the harms caused when abortion is banned is not “common sense”.

Post-Dobbs, polling shows that the vast majority of Americans want abortion legal: over 80% of Americans don’t want pregnancy to be legislated, 78% of Americans believe the decision to have an abortion should be left between the patient and doctor, and 7 in 10 voters support access to abortion medication. Republicans began to really embrace the stance that they believe in exceptions for abortions to make it seem like they are willing to compromise to appeal to moderate voters in the aftermath of the overturn of Roe v Wade. In reality, they aren’t compromising on “common sense” legislation – they’re compromising the health and well-being of the very people they’re claiming to protect.

Medical Misinfo: late-term abortion edition

In true Republican fashion, Mark mentions “late-term abortions” at the end of the ad. The anti-abortion movement thrives off of emotionally-inflammatory rhetoric and abortion stigma, which are two characteristics of the phrase “late-term abortion”. This was Mark’s subtle way of appealing to moderate voters with extremist policy that’s been rhetorically watered down to make it more palatable in order to gain votes come November.

“30 years ago, my wife and I made a very difficult decision – we had an abortion. It was like this solid pain between us that we never spoke of”. Then his wife, Yolanda Robinson, states “it’s something that stays with you forever”. Mark Robinson continues, “That’s why I stand by our current law. It provides commonsense exceptions for the life of the mother, incest, and rape which gives help to mothers and stops cruel late-term abortions. When I’m Governor, mothers in need will be supported.”

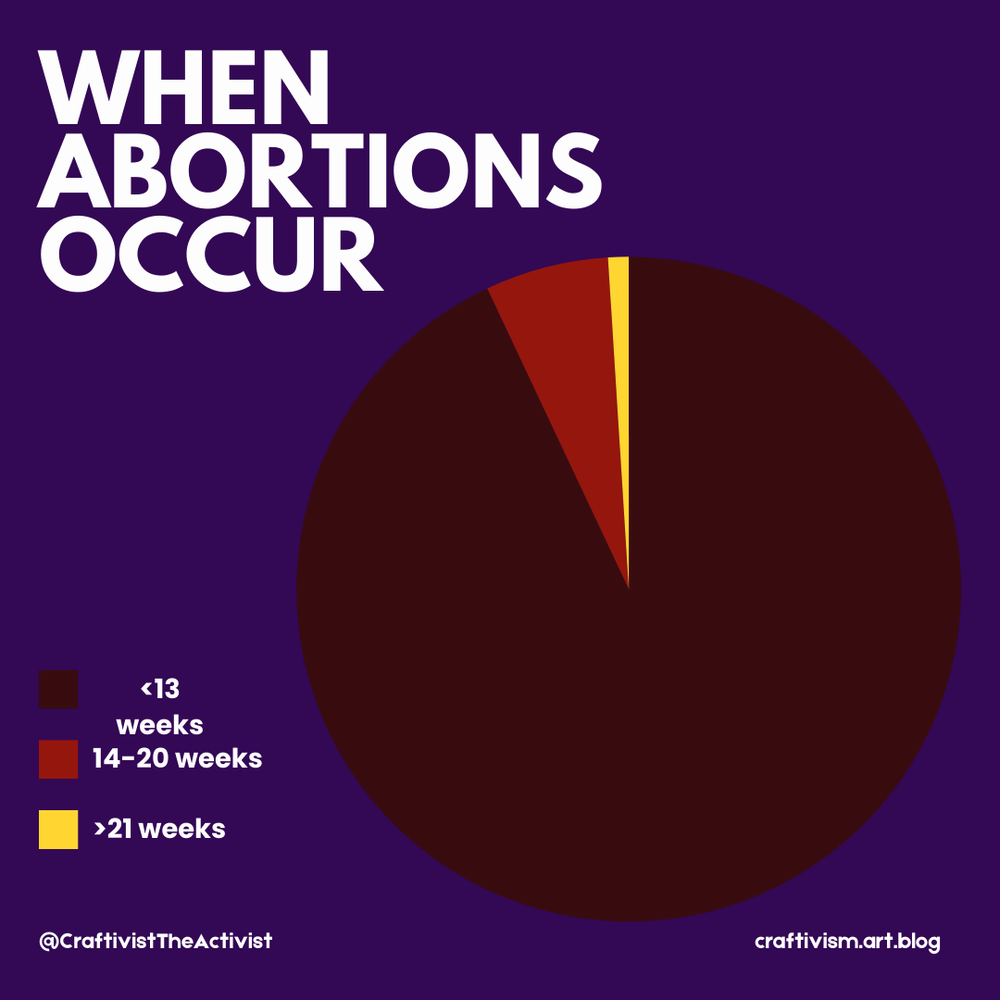

The phrase “late-term abortion” is a political buzzword that anti-abortion proponents have latched onto as a talking point to demonize abortions later in pregnancy when the vast majority (98.7%) of abortions are before 21 weeks. The anti-abortion movement has a reputation for using stigmatizing, emotionally-charged rhetoric to justify banning abortion and to ostracize the people who get and provide abortions. Anti-abortion opponents made up the phrase “late-term abortion” and embrace it because they define it however they want as a part of their language war.

According to experts like the American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology (ACOG), the term “late-term abortion” has no medical significance and is not used in a clinical setting or to describe the delivery of abortion care later in pregnancy. When health care providers use language like “full term” and “late term” in the context of pregnancy, they’re talking about how far along the pregnancy is (with “full term” meaning between 39 and 40 weeks and “late term” meaning 41+ weeks). It’s important to note that they do not use these terms to categorize types of abortion care.

The reasons people seek abortions later in pregnancy include medical concerns such as fetal anomalies or maternal life endangerment, as well as barriers to care that cause delays in obtaining an abortion. What’s cruel is delaying and denying people the healthcare they need.

Despite all this, leaders in the anti-abortion movement can’t even agree on exactly when a ‘late-term abortion’ supposedly happens. It seems to be determined by whatever Republican or anti-abortion organization writing the bill wants it to be.

For example, in 2021, congressional Republicans sponsored the Pain-Capable Unborn Child Protection Act (model legislation created by the National Right to Life Committee), a bill that determined abortions after 20 weeks to be “late-term”. The next year, they sponsored the “Protecting Pain-Capable Unborn Children from Late-Term Abortions Act,” that determined “late-term” after 15 weeks. The anti-abortion Charlotte Lozier Institute claims the phrase is appropriate for abortions performed after only 13 weeks of pregnancy.

Taking a page out of the playbook

Since abortion bans are highly unpopular and harmful, Mark Robinson is using the rhetorical tactics directly from the post-Dobbs playbook. It’s easier to fine-tune an extreme candidate’s political messaging in the months before the election than it is to address the wide-ranging devastation caused by their own policies that harm the people they claim to protect.

For years, Mark Robinson has been vocal about his anti-abortion stance by perpetuating abortion stigma and medical misinformation, and this pre-election rhetorical shift is no different. Don’t let him fool you. As he said, if it were up to him, we would have a total abortion ban with no exceptions. Remember this in November when you go to the voting booth, and remember to donate to the local abortion fund.

Read on Craftivist the Activist!

CVDSA’s Socialist Voter Guide for the August Primary

Our endorsed candidate

Vermonters will go to the polls on Tuesday, Aug. 13, to select the major parties’ nominees for the general election in November. The membership of the Champlain Valley Democratic Socialists of America voted to endorse just one candidate in the primary: Sen. Tanya Vyhovsky, an active member of our chapter and a powerful voice for Vermont’s working class.

The Chittenden-Central District consists of Winooski and Essex Junction, most of Burlington and Essex, and a sliver of Colchester. If you live here, we urge you to vote on the Democratic ballot for the Vermont Senate’s only Progressive and its only socialist (Tanya also received DSA’s national endorsement).

In the last biennium, Tanya helped win the Vermont PRO Act and a safe injection site in Burlington. She also spoke out for Palestinian liberation and recently sued the governor. She introduced bills to prevent the privatization of public services and to increase civilian oversight of the police, and while these didn’t pass, we know she won’t stop fighting for bold ideas.

A Republican-backed TV celebrity wants to cut short Tanya’s important work in Montpelier. Of the four Democratic competitors in Chittenden-Central, a three-seat district, newcomer Stewart Ledbetter, a tough-on-crime “moderate,” is easily the worst.

But thanks to the generosity of various landlords and business owners, Ledbetter has easily outraised all three incumbents combined. As Senate President Pro Tempore, Phil Baruth doesn’t appear to be at risk, but Sen. Martine Gulick, a self-proclaimed social democrat whom Tanya has called an ally, does.

Alongside Tanya, we recommend voting for Martine. A Democrat who just completed a productive first term in office, she introduced several minor but successful bills with unobjectionable aims, such as improving safety for road work crews, promoting doula services, and creating a pathway to legalization for psilocybin in therapeutic settings.

The Progressive slate

With our usual reservations, we also recommend the Vermont Progressive Party’s full 2024 slate, which includes four statewide candidates: Bernie Sanders for U.S. Senate, Esther Charlestin for Governor, David Zuckerman for Lieutenant Governor, and Doug Hoffer for State Auditor.

Zuckerman, the Progs’ standard-bearer, faces another well-funded challenger, Winooski Deputy Mayor Thomas Renner, whom the Democrats have identified as a rising star in their party. Renner has publicly positioned himself as a left-liberal – albeit one without Zuckerman’s stubborn hippie streak – but his top donors belong to the plutocratic Tarrant family, including a former Republican nominee for U.S. Senate who spent $6 million of his own money in a failed attempt to take down Bernie Sanders.

In the Champlain Valley, the Progs have endorsed three new candidates for State Representative: Larry Lewack in Chittenden-13, Missa Aloisi in Chittenden-17, and Chloe Tomlinson in Chittenden-21.

Of the three, Tomlinson seems to have the leftmost instincts on issues like climate and criminal justice. As one of two active candidates in a two-seat district in Winooski, she also has the easiest path to office, where she would replace outgoing Progressive Rep. Taylor Small. A CVDSA member, Nick Brownell, filed to appear on the ballot but later decided against campaigning this time.

Lewack, a founding member of the Progressive Party who works as a town planner, has a long track record of involvement in community and politics and, with Rep. Gabrielle Stebbins having declined to seek re-election in Burlington’s South End, a chance to claim an open seat. He faces two candidates with credible résumés of their own in a district that tends to favor traditional Democrats, but running principally on a promise of tax reform, Lewack has not presented himself as a radical.

Aloisi has to defeat a Democratic “incumbent” who, owing to a dirty move by Gov. Scott, took over Progressive Emma Mulvaney-Stanak’s House seat in the final weeks of the 2024 session, following her mayoral inauguration. With Mulvaney-Stanak’s endorsement, Aloisi aims to win a district that straddles Burlington’s Old North End and its New North End, combining disparate constituencies.

Socialism isn’t on the ballot in any of the abovementioned House races. But the campaigns by Tomlinson, Lewack, and Aloisi represent plausible opportunities for the Progressive Party to expand its footprint in Montpelier, as long as the three incumbent Progs running unopposed in Chittenden-15 and Chittenden-16 continue to caucus with the party. For opponents of the political duopoly that afflicts every US state except our own, this prospect has a value that hinges only in part upon the particular character of Vermont’s left-wing alternative.

Important policies like just cause eviction and paid family leave are also, to some degree, at stake. With Progressive candidates vying pragmatically to win the Democratic Party’s ballot line, be sure to vote in the Democratic primary. The names on the Progressive Party’s ballot, which exists purely as a legal requirement, are placeholders.

On Aug. 13, polling stations will open at 7 a.m. and close at 7 p.m.

Statement Re: COS DSA Passes a Resolution For an Anti-Zionist Colorado Springs DSA in both Principle and Practice

At our general meeting on July 28, we voted on and passed a resolution that states (among other things) our chapter’s commitment to:

Support the BDS movement and pro-Palestinian policy

Reject legislation and politicians that (aim to) provide material support for the zionist entity

Expel members that provide material support for the zionist entity

Denounce zionism as a racist, fascist, and colonial ideology

Denounce the zionist past of the DSA

Following the chaotic endorsement and subsequent un-endorsement of Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez (AOC) by DSA’s National Political Committee (NPC), despite AOC’s actions to support zionism and the zionist entity (read more about that here), we now join many other DSA chapters in passing resolutions inspired by Member Submitted Resolution 12 (MSR-12). The NPC tabled MSR-12 at the 2023 DSA national convention, and recently passed a significantly amended and watered down version of the resolution in July. Their amended version is different from ours in several ways. For example, theirs does not specify that chapters expel zionists from DSA, even after ample opportunity to learn about the Palestinian struggle and Palestinian liberation. We’re disappointed in the NPC’s choice to water down their resolution. With the landslide passage of our resolution (shown below) we call on the NPC to become committed to anti-zionism in accordance with DSA’s stated values and, if our chapter is any indication, the values of the huge majority of DSA members.

The full text of our resolution is as follows:

Whereas, and in line with Convention Resolutions #4 and #62 from 2019, the Democratic Socialists of America (DSA) is an anti-imperialist organization;

Whereas, and in line with Convention Resolution #50 from 2019, the DSA is an anti-colonialist organization committed to advancing decolonization projects;

Whereas, and in line with Convention Resolutions #41 and #45 from 2017 and Resolutions #4 and #31 from 2021, the DSA is an anti-racist organization;

Whereas, and in line with Convention Resolutions #7&8 from 2017 and Resolution #35 from 2019, DSA National has publicly declared on numerous occasions in recent years that it “unapologetically stands in solidarity with Palestinian people everywhere;”

Whereas, Zionism – as popularized by Theodore Herzl and explicitly described by him as “something colonial,” meant to be “a wall of Europe against Asia… an outpost of [Western] civilization against [Eastern] barbarism” – is and has always been a racist, imperialist, settler-colonial project that has resulted in the ongoing death, displacement, and dehumanization of Palestinians everywhere (i.e., in Palestine and in diaspora around the world);

Whereas, the establishment of a Jewish ethnostate in Palestine (i.e., the so-called “state of Israel”) and its maintenance via ongoing and illegal occupation, apartheid and ethnic cleansing represent the culmination of Zionists’ century-long colonization of Palestine;

Whereas, and antithetical to the DSA’s contemporary principles and policies, DSA’s founding merger was heavily predicated on ensuring that the DSA would uphold Democratic Socialist Organizing Committee’s position of supporting continued American aid for Israel’s Zionist settler-colonial project, as explicitly noted in our organization’s founding merger documents (e.g., Points of Political Unity) and by Michael Harrington himself in his autobiography;

Whereas, and antithetical to the DSA’s contemporary principles and policies, a number of DSA endorsed electeds (e.g., Jamaal Bowman & Nithya Raman) have consistently demonstrated a commitment to Zionism through their public opposition to BDS and/or support for legislation that harms Palestinians everywhere (e.g., public support for and votes in favor of U.S. financial aid to the Israeli military, which forcefully advances the ongoing ethnic cleansing of Palestine through systematic tactics of abuse, forcible displacement, and murder of Palestinians; governmental adoption of definitions of antisemitism that conflate anti-Zionism and antisemitism, leading to the suppression of speech of Palestinians and those in solidarity with them);

Whereas, the DSA’s historic and contemporary association with and enablement of Zionism has jeopardized DSA rank-and-file membership’s confidence in the integrity of DSA’s overall politics, as well as our organization’s working relationships with major Palestinian-led grassroots organizations across North America;

Whereas, DSA membership has overwhelmingly denounced Zionism through its stated principles and convention mandates since 2017 but has yet to articulate these newfound principles into a more coherent praxis;

Whereas, the resolution “Make DSA an Anti-Zionist Organization in Principle and Praxis” (MSR #12), failed to be heard or deliberated on at the 2023 National Convention, and there is an urgent need to address this on a chapter level;

Whereas, in failing to pass an Anti-Zionist resolution in the spirit of MSR #12, DSA is not a safe space for Palestinians and those who organize for Palestinian liberation, as evidenced by the digital and physical threats against Palestine organizers at the 2023 convention;

Therefore, be it resolved, the Colorado Springs DSA chapter denounces the organization’s Zionist roots and reaffirms its commitment to being an anti-racist, anti-imperialist organization by explicitly committing to being an anti-Zionist chapter– in both principle and praxis;

Be it resolved, Colorado Springs DSA once again reaffirms our organizations commitments to Palestinian liberation and the broad, international BDS movement by conveying our expectation that all of Colorado Springs DSA’s endorsed candidates hold true to the following basic commitments:

Publicly support the Boycott, Divestment and Sanctions (BDS) movement;

Refrain from any and all affiliation with the Israeli government or Zionist lobby groups, such as, but not limited to, AIPAC, J Street, or Democratic Majority for Israel (DMFI), including participating in political junkets or any event sponsored by these entities;

Pledge to oppose legislation that harms Palestinians, such as…

Any official adoption of a redefinition of antisemitism to include opposition to Israel’s policies or legal system, or support for BDS (e.g., IHRA definition of antisemitism);

Legislative and executive efforts to penalize individuals, universities and entities that boycott Israel;

Legislative and executive efforts to send any military or economic resources to Israel;

Pledge to support legislation that supports Palestinian liberation, such as…

Legislative and executive efforts to end Israeli apartheid and ethnic cleansing against Palestinians and promote Palestinians’ rights to return to and live freely on the land (e.g., H.R. 3103 (118th Congress));

Condemnation of Israeli apartheid and colonial practices (e.g., H.Res. 751);

Attempts to end the spending of U.S. tax dollars on Israel and/or sanction Israel until it ceases its practices of apartheid and colonialism;

Be it resolved, our local chapter’s candidate questionnaires will continue to include a question that inquires about the candidate’s position on BDS;

Be it resolved, potential candidates who cannot commit to the aforementioned basic expectations will be disqualified from endorsement by the Colorado Springs DSA at every level;

Be it resolved, the Colorado Springs DSA, in collaboration with trusted Palestine Solidarity movement partners in the grassroots (e.g., Palestinian Youth Movement) and the DSA International Committee, will provide all endorsed candidates with anti-Zionist educational materials, 1-to-1 training opportunities and ongoing, open-door counsel as needed;

Be it resolved, upon receiving fair and ample opportunity for education about the Palestinian struggle for liberation, endorsed candidates who do not commit to the aforementioned basic expectations will have their Colorado Springs DSA endorsements swiftly revoked;

Be it resolved, Colorado Springs DSA members – regardless of endorsement status – who are credibly shown to:

have consistently and publicly opposed BDS and Palestine (e.g., denouncing the BDS movement in public interviews; writing public op-eds denouncing the BDS movement; drafting and voting in favor of legislation that suppresses BDS, such as legislation that suppresses speech rights around the right to freely criticize Zionism/Israel and/or the right to boycott), even after receiving fair and ample opportunity for education about the Palestinian struggle for liberation,

be currently affiliated with the Israeli government or any Zionist lobby group(s) such as, but not limited to, AIPAC, J Street, or Democratic Majority for Israel (DMFI), or

have provided material aid to Israel (e.g., Congresspeople voting to provide Israel with material aid; gave direct financial donations of any kind to Israel and/or settler NGOs who carry out the mission of Israeli settlement and Palestinian dispossession/displacement, such as the Jewish National Fund, the Israel Land Fund, the Hebron Fund, and Regavim)

will be considered in substantial disagreement with DSA’s principles and policies, and thus, the chapter will initiate the expulsion process in line with Article 1, Section 3 of the national DSA Bylaws;

Be it resolved, members expelled on these grounds may be reconsidered for membership reinstatement once per year provided they write a statement to chapter membership that 1.) demonstrates a basic understanding of Palestinian issues and Zionism and 2.) apologizes for past anti-solidaristic behaviors with a commitment to putting their new anti-Zionist principles into practice;

Be it resolved, membership reinstatement of reformed Zionists will require recommendation for reinstatement by their local chapter, followed by a majority vote in favor of reinstatement by the National Political Committee, as per the national Bylaws.

WE WON! A clean sweep for the Protect the People’s Voice Coalition!

WE WON! The people of Johnson City have chosen to retain the democratic rights that are written into the Johnson City charter. Together, we’ve sent a message to the Johnson City Board of Commissioners that says:

- We want more, not fewer, opportunities to see the proposed budget before it’s passed.

- We want more, not less, time to prepare for public hearings on ordinances that affect our neighborhoods and communities.

- We want city jobs to continue to be good, stable jobs.

- We want city elections to be held on a day that more–not fewer–people vote, we don’t want the 2026 city elections canceled, and we don’t want commissioners to receive nearly two-year extensions of their terms.

We can, however, go farther than maintaining the status quo. Here is a vision forward on each of these issues:

- The city’s board of commissioners should strive to make sure residents are more, not less, able to understand the city budget and its impact. Nashville’s Citizens’ Guide to the Metro Budget is a good model to start with. This is an important step our city government can take toward the People’s Budget that our city should run on.

- Public meetings of all city boards need to be more, not less, accessible. All public board meetings–not just the commission meetings–should be livestreamed and made available for later watching. Childcare should be made available during board meetings. Participation in public hearings and public comment periods of board meetings should be extended to virtual attendees.

- Our city should go out of its way to protect its workers and its good city jobs. One thing the board of commissioners and city manager could do in this direction is enshrine protections for LGBTQ workers in the city’s policies. We would also love to hear from city workers what they need.

- In voting to put these questions on the ballot our city commissioners said that one reason they wanted to move city elections from November to August because the current election schedule was confusing to voters. If commissioners are truly committed to making elections less confusing to voters, they will work with the surrounding counties to move county general elections to November. When all of the primary races, from local to federal*, are on the August ballot, and all of the general races, from local to federal, are on the November ballot, elections will be much clearer to everyone. The city can also help with voter turnout at all elections by using their website, newsletter, and access to the press to educate voters on which offices are up for election when and what the responsibilities and functions of those offices are.

How do we get there?

- Get Organized. This campaign would never have gotten off the ground had some of us not been organized before the Commissioners introduced their ballot questions. We would have been caught off guard and unable to respond quickly. If you want to see more wins like this in the future, get organized. Join (or form) a union. Join a community group. Why not try out DSA?

- Vote Them Out. This November, vote out the three commissioners who are up for re-election. Each one of them was fully in support of these amendments to reduce accountability, transparency, and public engagement. Red-baiting Todd Fowler, Joe Wise, and Aaron Murphy don’t need another term in office. In 2026–an election that would not be happening had these amendments passed–vote out Jenny Brock and John Hunter as well.

- Write Your County Commissioners. Let’s do what really makes sense and move the county general elections to November with all the other general elections, and the county primaries to August with all the other primaries. (Find your district using this map.)

- Build a People’s Voice for a People’s Budget. We are working to build a People’s Budget for JC that prioritizes the needs of working people over those of outside development firms, the Ballad Health monopoly, and other special interests. City officials should be asking rather than telling us how our money will be spent. The good thing is, we don’t have to wait for city officials. We can do it ourselves. Fill out the People’s Budget Survey to let us know your priorities for city spending.

Our victorious campaign to Protect the People’s Voice has shown us that people power can overcome the power of monied interests. Let’s not let up now! Let’s continue to organize so we can build a Johnson City and a Northeast Tennessee for all!

*Excluding the presidential primary, for which an August primary would be too late for party conventions.

Peninsula DSA Supports Single Inclusive Democratic State for Palestinians and Israelis

Peninsula DSA Supports Single Inclusive Democratic State for Palestinians and Israelis

SAN MATEO, July 16, 2024 - Following the leadership of our comrades in Chicago DSA, Peninsula (CA) DSA voted at our June 2024 General Membership Meeting to declare our support for a political vision of one democratic state in Palestine. We identify Zionism’s politicization of identity and Israel’s nature as a state exclusive to Jews as a root cause of the suffering and injustice which Israel has inflicted upon the people of Palestine, and we believe that true peace and liberation can only be achieved by the dismantling of the apartheid, settler-colonial state and the establishment of one democratic state in its stead.

The material reality is that a two-state solution is not feasible, and it has long been more of an aspirational myth rather than a serious policy proposal. In the words of Jewish Currents contributing editor Joshua Leifer, the idea is little more than a “political fiction” which gives liberal Zionists a way “to reconcile their seemingly contradictory commitments to both ethnonationalism and liberal democracy.” Since the 1970s, when Palestinian intellectuals first proposed a “mini-state” on 22% of historic Palestine, Israel has continuously redefined the conceptual Palestinian state to include ever-less territory and to hold ever-less sovereignty. By the 1980s, there were already 100,000 Jewish settlers in the West Bank, prompting former Jerusalem Deputy Mayor Meron Benvenisti to warn that it was “five minutes to midnight” for the two-state solution. Now, there are over 650,000 settlers in the West Bank, and settlers, emboldened by Israel’s ongoing genocide in Gaza, are committing even more violence and stealing more Palestinian land. The two-state solution—which has come to mean a fragmented Palestine under de facto Israeli control—cannot generate a movement powerful enough to bring liberation to Palestine; it only provides cover for ongoing ethnic cleansing.

For this reason we support a movement for a single, inclusive state between the river and the sea that is:

- Democratic. All citizens would be equal in the eye of the state, including its laws, institutions and policies, regardless of identity. This includes the right of those who have been ethnically cleansed from Palestine to return and enjoy full citizenship.

- Secular. Freedom of worship would be guaranteed, and one’s religion or identity would not be a factor in granting or denying rights to citizens or non-citizens.

- Socially just. Stolen land, homes and property would be restituted to all victims of dispossession. Resources and social welfare would be allotted fairly to all citizens. The income, poverty and education gaps would be bridged.

Finally, we call on national DSA to likewise declare its support of one democratic state in Palestine: a “one-person, one-vote” state in which everyone is represented equally, regardless of ethnicity, religion, origin, etc. As socialists it is our responsibility to imagine what a just world would look like and share that vision with the world. Without democracy, self-determination is impossible, and without full equal rights under a secular state, there can be no democracy for the Palestinian people. Separate can never be equal.

Further reading:

- “What Does ‘From the River to the Sea’ Really Mean?” (2021), Jewish Currents

- “Teshuvah: A Jewish Case for Palestinian Refugee Return” (2021), Jewish Currents

- The Resilient Fiction of a Two-State Solution” (2020), Jewish Currents

- “Yavne: A Jewish Case for Equality in Israel-Palestine” (2020), Jewish Currents

- “The Case for the One Democratic State Initiative as a Counter-Hegemonic Endeavor” (2023), Mondoweiss

- One Democratic State Initiative