Taxing the rich: CA DSA Endorses the 2026 Billionaire Tax Act and the Children’s Education and Health Care Protection Act of 2026

California DSA delegates, representing chapters from across the state, have recently voted to endorse the Billionaire Tax Act and the Children's Education and Health Care Protection Act, under a unified campaign to ‘Tax the Rich’.

The Billionaire Tax Act would levy a one-time 5% tax on individuals worth more than $1 billion in order to offset the loss of almost $100 billion of federal funding towards Californian healthcare. Without this funding, thousands of jobs will be lost, millions of Californians could lose coverage altogether, and care facilities across the state could be forced to close.

The Children’s Education and Health Care Protection Act would ensure the continuation of the temporary income tax imposed on the top 2% of income earners by CA’s Proposition 55 in 2016. This tax raises between $5 billion and $12 billion each year for children’s education and health care—the loss of that funding would be catastrophic.

The success of both measures would provide much-needed funding to California’s essential services. Thus, California DSA delegates voted to endorse both under a unified campaign to ‘Tax the Rich’.

The gap between the billionaires and the rest of us has never been wider. It is time for the wealth taken from workers to be invested back into our state, to fund our hospitals, schools, and essential services. It’s time to tax the rich.

Weekly Roundup: February 17, 2026

Events & Actions

Tuesday, February 17 (5:30 PM – 7:00 PM):

Tuesday, February 17 (5:30 PM – 7:00 PM):  Social Housing Meeting (zoom and in person at 1916 McAllister St)

Social Housing Meeting (zoom and in person at 1916 McAllister St)

Tuesday, February 17 (7:00 PM – 8:00 PM):

Tuesday, February 17 (7:00 PM – 8:00 PM):  Public Transit Meeting (zoom and in person at 1916 McAllister St)

Public Transit Meeting (zoom and in person at 1916 McAllister St)

Wednesday, February 18 (6:00 PM – 7:30 PM):

Wednesday, February 18 (6:00 PM – 7:30 PM):  What Is DSA? (1916 McAllister St)

What Is DSA? (1916 McAllister St)

Thursday, February 18 (6:00 PM – 7:00 PM):

Thursday, February 18 (6:00 PM – 7:00 PM):  Social Committee Meeting (zoom)

Social Committee Meeting (zoom)

Thursday, February 18 (7:00 PM – 11:00 PM):

Thursday, February 18 (7:00 PM – 11:00 PM):  UESF x DSA SF Strike Victory Social (Molotov’s, 582 Haight St)

UESF x DSA SF Strike Victory Social (Molotov’s, 582 Haight St)

Thursday, February 19 (3:00 PM – 5:00 PM): Rally w/ California Nurses Association: Keep ICE Out of Hospitals (UCSF Parnassus Campus, 505 Parnassus Ave)

Thursday, February 19 (3:00 PM – 5:00 PM): Rally w/ California Nurses Association: Keep ICE Out of Hospitals (UCSF Parnassus Campus, 505 Parnassus Ave)

Thursday, February 19 (6:30 PM – 7:30 PM):

Thursday, February 19 (6:30 PM – 7:30 PM):  Public Bank Project Meeting (zoom)

Public Bank Project Meeting (zoom)

Thursday, February 19 (7:00 PM – 8:00 PM): Immigrant Justice Working Group Meeting (zoom and in person at 1916 McAllister St)

Thursday, February 19 (7:00 PM – 8:00 PM): Immigrant Justice Working Group Meeting (zoom and in person at 1916 McAllister St)

Friday, February 20 (9:30 AM – 10:30 AM):

Friday, February 20 (9:30 AM – 10:30 AM):  District 1 Coffee with Comrades (Breck’s, 2 Clement St)

District 1 Coffee with Comrades (Breck’s, 2 Clement St)

Saturday, February 21 (11:00 AM – 2:00 PM):

Saturday, February 21 (11:00 AM – 2:00 PM):  ETOC Session 3 – Building Campaigns II (1916 McAllister St)

ETOC Session 3 – Building Campaigns II (1916 McAllister St)

Saturday, February 21 (11:00 AM – 1:00 PM):

Saturday, February 21 (11:00 AM – 1:00 PM):  Public Bank Lit Drop – Alamo Square (Hayes Street & Scott Street)

Public Bank Lit Drop – Alamo Square (Hayes Street & Scott Street)

Saturday, February 21 (6:00 PM – 8:00 PM):

Saturday, February 21 (6:00 PM – 8:00 PM):  HWG Food Service (Castro Street & Market Street)

HWG Food Service (Castro Street & Market Street)

Sunday, February 22 (1:30 PM – 3:00 PM):

Sunday, February 22 (1:30 PM – 3:00 PM):  Get to Know EWOC!

Get to Know EWOC!  (1916 McAllister St)

(1916 McAllister St)

Sunday, February 22 (5:00 PM – 6:00 PM):

Sunday, February 22 (5:00 PM – 6:00 PM):  Tenderloin Healing Circle Working Group (zoom)

Tenderloin Healing Circle Working Group (zoom)

Monday, February 23 (6:00 PM – 8:00 PM):

Monday, February 23 (6:00 PM – 8:00 PM):  Tenderloin Healing Circle (Kelly Cullen Community, 220 Golden Gate Ave)

Tenderloin Healing Circle (Kelly Cullen Community, 220 Golden Gate Ave)

Monday, February 23 (6:30 PM – 7:30 PM):

Monday, February 23 (6:30 PM – 7:30 PM):  DSA Run Club (McClaren Lodge, Golden Gate Park)

DSA Run Club (McClaren Lodge, Golden Gate Park)

Monday, February 23 (7:00 PM – 8:00 PM): Labor Board Meeting – UESF Strike Support Retrospective (zoom and in person at 1916 McAllister St)

Monday, February 23 (7:00 PM – 8:00 PM): Labor Board Meeting – UESF Strike Support Retrospective (zoom and in person at 1916 McAllister St)

Tuesday, February 24 (6:30 PM – 7:30 PM): Ecosocialist Bi-Weekly Meeting (zoom and in person at 1916 McAllister St)

Tuesday, February 24 (6:30 PM – 7:30 PM): Ecosocialist Bi-Weekly Meeting (zoom and in person at 1916 McAllister St)

Wednesday, February 25 (6:45 PM – 8:30 PM): Tenant Organizing Working Group Meeting (zoom and in person at 438 Haight St)

Wednesday, February 25 (6:45 PM – 8:30 PM): Tenant Organizing Working Group Meeting (zoom and in person at 438 Haight St)

Thursday, February 26 (6:00 PM – 7:00 PM):

Thursday, February 26 (6:00 PM – 7:00 PM):  Education Board Open Meeting (zoom)

Education Board Open Meeting (zoom)

Thursday, February 26 (7:00 PM – 8:30 PM):

Thursday, February 26 (7:00 PM – 8:30 PM):  ICE Out Orientation (zoom and in person at 1916 McAllister St)

ICE Out Orientation (zoom and in person at 1916 McAllister St)

Saturday, February 28 (11:00 AM – 2:00 PM):

Saturday, February 28 (11:00 AM – 2:00 PM):  ETOC Session 4 – From Organizing Committee to Mass Organization (1916 McAllister St)

ETOC Session 4 – From Organizing Committee to Mass Organization (1916 McAllister St)

Saturday, February 28 (11:00 AM – 1:00 PM):

Saturday, February 28 (11:00 AM – 1:00 PM):  Physical Education + Self Defense Training (Kelly Cullen Community, 220 Golden Gate Ave)

Physical Education + Self Defense Training (Kelly Cullen Community, 220 Golden Gate Ave)

Saturday, February 28 (1:00 PM – 4:00 PM):

Saturday, February 28 (1:00 PM – 4:00 PM):  DSA SF at Alemany Farm (Alemany Farm, 700 Alemany Blvd)

DSA SF at Alemany Farm (Alemany Farm, 700 Alemany Blvd)

Sunday, March 1 (2:00 PM – 3:30 PM):

Sunday, March 1 (2:00 PM – 3:30 PM):  What Is DSA? (Ortega Branch Library, 3223 Ortega St)

What Is DSA? (Ortega Branch Library, 3223 Ortega St)

Sunday, March 1 (11:00 AM – 1:00 PM):

Sunday, March 1 (11:00 AM – 1:00 PM):  Sip ‘n’ Stitch (TBD)

Sip ‘n’ Stitch (TBD)

Monday, March 2 (6:30 PM – 8:00 PM): Homelessness Working Group Regular Meeting (zoom and in person at 1916 McAllister St)

Monday, March 2 (6:30 PM – 8:00 PM): Homelessness Working Group Regular Meeting (zoom and in person at 1916 McAllister St)

Monday, March 2 (7:00 PM – 8:00 PM): Labor Board – Flex Meeting (zoom)

Monday, March 2 (7:00 PM – 8:00 PM): Labor Board – Flex Meeting (zoom)

Check out https://dsasf.org/events for more events and updates.

When We Fight, We Win!

Last Friday, after 4 days of striking by UESF educators, UESF finally reached a tentative agreement! WE WON!!

When we got word about the strike, DSA SF jumped into action, raising over $19,000 to fund strike support and hundreds of DSA members marched, showed up at picket lines, cooked for students while schools were closed, and brought supplies and meals to fuel strikers in their fight for better working conditions and for public education.

With the money raised, DSA SF served more than 2,000 meals to students and to strikers on the picket line. Socialists in San Francisco stand with organized workers and are prepared to materially support workers in their fight for fair wages and working conditions!

Join us at the following events to celebrate our contributions to this historic victory with our union comrades and to discuss follow up steps with the labor board!!

- Wednesday, February 18th at 7 PM – Joint Social with UESF @ Molotov’s RSVP here

- Monday, February 26th at 6-8 PM – Bread For Ed Retrospective at our regular Labor Board Meeting

Power to the educators! Power to the workers!

UCSF Parnassus Day of Action

On Thursday, February 19, union nurses across the country will join in a day of action to protest the increased presence of ICE in our communities and to demand that our patients and their families are safe and protected. As nurses, we care for everyone despite immigration status.

We call on UC to comply with the law, provide clear guidelines on what to do if ICE enters our facilities, and always put patients’ safety and security first.

Stand in solidarity to protect our patients and community! Join us at UC Parnassus (505 Parnassus) on Thursday, February 19 at 3 PM. RSVP here

Our member Luis will be speaking, so show up and wear your DSA swag!

SF Public Bank Lit Drop

Please join the Ecosocialist Working Group and the SF Public Bank Coalition for a lit drop event this upcoming Saturday, February 21st. We’ll be meeting at Alamo Square Park (Scott and Hayes). No experience needed and snacks will be provided. We’re planning on meeting up afterwards for food and drink. RSVP here

Get to Know EWOC!

Get to Know EWOC!

Overworked, underpaid, and fed up with your working conditions? Interested in learning what it means to unionize your workplace? Come talk to organizers and volunteers from the San Francisco local of the Emergency Workplace Organizing Committee (EWOK)!

We’ll be at 1916 McAllister from 1:30 to 3PM on Sunday, February 22nd. RSVP here

The Emergency Workplace Organizing Committee (EWOC) is a volunteer-run network of hundreds of workers, organizers, and supporters who together are building a stronger, worker-led labor movement. We support and train any non-union worker in any industry who wants power and agency at work. Along with unions and other labor organizations, we can build the militancy and strength of the working class and effectively organize the millions of unorganized workers in the United States.

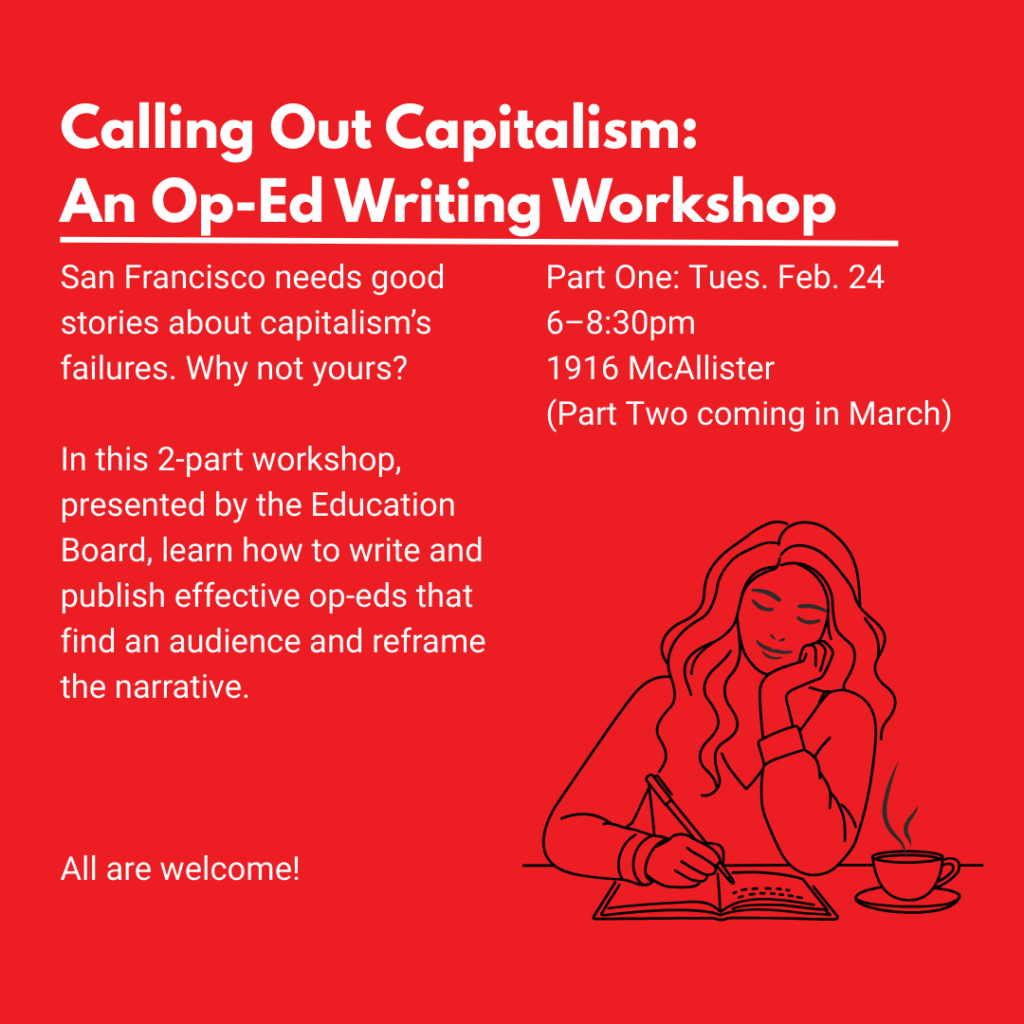

Calling Out Capitalism: An Op-Ed Writing Workshop

Back by popular demand, Ed Board has set dates for the next round of Op-Ed Writing Workshops! Part One is coming up on Tuesday, February 24 at 6PM. Held in-person at 1916 McAllister. RSVP here

We’ll cover techniques and strategies for writing effective op-eds, and lead some writing activities to get you crafting op-eds of your own. Part Two, a workshop to give/get peer feedback on your op-ed drafts, is up in March. Stay tuned for details!

ICE Out of SF: Plug in and Strategize!

We’ll be strategizing, and connecting the various initiatives happening across the city.

This is a great event for people already involved in immigrant protection to expand their work, as well as for folks looking to get plugged in.

Some of the initiative we’ll discuss are: Adopt-A-Corner, Court watch, Accompaniment, Know Your Rights canvassing, and more!

Join us at 1916 McAllister St on Thursday, February 26 at 7 PM. RSVP here

Grow Community with the DSA at Alemany Farm

Come join DSA SF’s Ecosocialist working group on Saturday, February 28th at 1:00 PM at one of San Francisco’s community gems, Alemany Farm.

This is a great event for both new members and long-time DSA members. Come expand your ecological consciousness and spend an afternoon with knowledgeable urban agriculturalists and fellow comrades. Email ecosocialist@dsasf.org with any questions. RSVP Here

Emergency Tenant Organizing Committee (ETOC) Fundamentals of Tenant Organizing Watch Party

Looking to deepen your understanding of housing work on the ground? Interested in building durable tenant power in SF? Come learn how to organize tenant associations, fight landlords collectively, and build toward radical tenant unionism in San Francisco. These ETOC watch parties happen every Saturday in February at 11:00 AM at our office (1916 McAllister) and focus on turning socialist analysis into mass tenant struggle: investigation, campaigns, and building real tenant organizations that can win. If you’re serious about anti-landlord work, this is where to plug in.

Thank You Kelly Cullen Community Cleaning Comrades!

On Friday the 13th (spooky~), Tenderloin Healing Circle hosted a café cleaning event at Kelly Cullen Community!! This mutual aid action allowed us to show our gratitude to KCC for allowing us to use the auditorium for chapter meetings, TLHC, and Phys Ed; as well as help provide a clean and cozy space for residents to hang out.

A mighty crew of 9 spent 2 hours sorting, bagging and boxing all the supplies so the building manager can start setting up supply stations and get a sense for what inventory they have available. The Tenderloin Healing Circle will also be hosting a follow-up event to help the building manager set up a linen closet with the supplies we helped organize, so keep an eye out for that!

Thank you again to everyone who showed up and helped!

Behind the Scenes

The Chapter Coordination Committee (CCC) regularly rotates duties among chapter members. This allows us to train new members in key duties that help keep the chapter running like organizing chapter meetings, keeping records updated, office cleanup, updating the DSA SF website and publishing the weekly newsletter. Members can view current CCC rotations.

Interested in helping with the newsletter or other day-to-day tasks that keep the chapter running? Fill out the CCC help form.

Citizen Spectators

by Jean Allen

Today, in the early hours of January 3rd, 2026, Donald Trump ordered the bombing of Caracas and the kidnapping of Venezuelan president Maduro as well as the first lady. This international smash and grab succeeded where twenty years of sanctions and international law couldn’t. As of the 3rd, the Bolivarian republic seems decapitated, and President Trump is openly speaking of taking Venezuelan oil.

The first political action I ever took was when my dad brought me to the 2003 protest against the Iraq War in New York City. It was the first time I’ve felt something I have felt so many times since–that I was within history, that I was doing something important with hundreds of thousands of other people. The 2003 protests were organized by the ANSWER coalition, a mix of socialist sects and newly mobilized liberals. ANSWER hoped to replicate the Vietnam-era protests against the war, and in terms of pure numbers they beat them. More Americans marched in 3/2003 than they ever had for any cause before.

In a way, those protests had an effect on the US state, just not the one wished for by the protestors. By 2003, the government had spent 30 years insulating foreign policy from popular discontent, by removing the draft and having our incursions short and based on air warfare. The opposition to Bush’s wars accelerated this process, as our military became focused on a small group of special forces ‘operators’ and mercenaries drawn from a smaller and smaller portion of the United States.

At this point, the President and his appointees are the only people who truly get to decide anything about our foreign policy. The president comes to power via indirect and relatively low-participation elections. In both elections Trump won, “Did Not Vote” would have beaten him and his opponent. This is in keeping with the vision our founders had of an executive with the power to interact with foreign kings, insulated from the will of the popular classes.

Because of this insulation, the relation most American citizens have to US foreign policy is that of spectators. We watch the TV show, we have opinions on it, we argue with each other about those opinions. Maybe we attend a rally, maybe we sign a statement, maybe we get our union to sign a statement, maybe we do a direct action which will affect .1% of the military materiel produced. Zooming out, for most people politics means arguing with family members about the TV show. But none of those things matter, none of those touch power. And so we spend most of our time arguing with each other about the TV show we’re all watching, because that feels like power. The Anti-Iraq War coalition fell apart under that tension, and the life of any activist is full of examples of infighting because of this.

I want to be clear that I view every single person who’s organized against the military as a hero. And I do not say this to demoralize. But we need to start planning at the scale we need to, and acknowledging the insufficiency of the tools we have against our undemocratic and colonial government is the first step to that. Our unions are an order of magnitude smaller and less militant than we need. Our rallies next to empty federal buildings are ignored. Our direct actions are affecting a small portion of the military industrial complex. Our international organization is effectively nonexistent. Socialists can only meaningfully elect federal-level politicians in a handful of places, and too often, anti-imperialism has been seen as a luxury belief unrelated to the socialist aim of affordability. Malcolm Harris said the day before Trump’s attack, “What’s the point of wanting to take power if you can’t?” That perspective, that we are arguing for nothing, has been a healthy counter to the crab-in-a-bucket instinct to infight since we can’t do much. Even the gesture at innovating new tactics feels like sand in my mouth. But it accepts that we will always be infantilized, always be spectators, in a way that feels disgusting now.

We have the tactics, we know the goal: organize the working class and the oppressed together to win a society where we can rule. But we do not have a plan at the scale we need to prevent the world from being brought down alongside the death throes of our declining empire. While we often talk about raising consciousness or educating the masses, popular opinion is on our side, both regarding socialism and against Trump’s suicidal adventurism. These opinions do not get to be expressed in our political system, so what DSA must focus on, in 2026 and 2028 and going forward, is voting in a bloc of congressional legislators who will be a consistent voice against militarization. We must do this because the attacks on Venezuela are accelerating a worldwide move towards increased militarization powered by world-destroying arms; and every dollar spent on guns, tanks, and aircraft is money not spent on the hospitals, schools, and environmental protections we’ll need in our hotter and hotter world. We have few chances to stop this, and we must prepare on a larger scale for the first opportunity.

The post Citizen Spectators first appeared on Rochester Red Star.

Break the ICE: Accountability for ICE

Tell Gov Whitmer to support AG Nessel’s Anonymous ICE Reporting Platform!

In the wake of ICE’s murderous campaign to kidnap our neighbors and restrict our Constitutional rights, we call on Governor Whitmer to support Attorney General Nessel’s recently launched anonymous reporting platform. We call on Whitmer to form an accountability commission to review ICE’s many crimes and constitutional violations. This group of masked secret police has been terrorizing communities with impunity for far too long.

Michigan will not be safe until we know that we have the ability to hold ICE accountable for their many assaults upon our communities and country. Our residents must also be able to do so knowing they are protected by our State from what has been proven to be an extremely corrupt and vengeful Trump regime.

- Anonymity & Privacy Protection: Individuals can now report misconduct without revealing their identity or contact information.

- Secure Evidence Submission: Photos, videos, and documents can now be submitted securely to protect the integrity of the evidence.

- Independent Oversight: Reports MUST be reviewed by an impartial body, ensuring transparency and fairness in the investigative process.

- Legal Protections for Whistleblowers: Michigan residents who report abuses MUST be protected by state and federal whistleblower laws.

- Collaboration with Advocacy Groups: The platform MUST work closely with civil rights organizations to ensure that the process remains accessible, credible, and effective.

The post Break the ICE: Accountability for ICE appeared first on Grand Rapids Democratic Socialists of America.

Abolish DHS: An Urgent, Winnable and Strategic Demand

From Intention to Impact

So You Chose to Have Kids At the End of the World