Your National Political Committee newsletter — Ideas into Action

Enjoy your August National Political Committee (NPC) newsletter! Our NPC is an elected 27-person body (including two YDSA members who share a vote) which functions as the board of directors of DSA. This month, you can welcome the new NPC, watch Rep. Rashida Tlaib’s electrifying speech, check out the Convention results, and get involved in DSA work!

And to make sure you get our newsletters in your inbox, sign up here! Each one features action alerts, upcoming events, political education, and more.

First off, we’d like to send a warm hello and gratitude to you for trusting us to be your national co-chairs for the next two years. This is a critical time for DSA, as we face down increasing fascism at home, militarism abroad, and the ticking clock of climate catastrophe. But we also continue to ride a wave of sustained membership growth, an increase in new DSA chapters and organizing committees, electoral wins, labor movement solidarity, and a general mood of excitement about the possibility of a democratic socialist future, one in which no one profits from the exploitation of another person. We are committed to working together alongside you all to level up DSA’s capacity, strength, and clarity of purpose as we build our fighting organization into the mass party that the moment demands.

We’d also like to congratulate our new fellow National Political Committee members, who were elected at our 2025 Convention earlier this month to a newly expanded NPC. They are:

- Christian A. (Long Island DSA)

- Eleanor B. (NYC-DSA)

- Hayley B.B. (Portland DSA)

- Jeremy C. (NYC-DSA)

- Cliff C. (Orlando DSA)

- Sidney C.W. (NYC-DSA)

- Kareem E. (NYC-DSA)

- Cerena E. (Houston DSA)

- Abdullah F. (DSA-LA)

- Frances G. (DSA-LA)

- Ahmed H. (NYC-DSA)

- David J. (NYC-DSA)

- John L. (New Orleans DSA)

- Francesca M. (Connecticut DSA)

- Luisa M. (Portland DSA)

- Sarah M. (Portland DSA)

- Clayton R. (DSA-LA)

- Katie S. (Ithaca DSA)

- Ella T. (Seattle DSA)

- Andrew T. (Denver DSA)

- Cara T. (Metro Detroit DSA)

- Amy W. (Seattle DSA)

- Hazel W. (DSA SF)

Congratulations to all and we look forward to working with you!

The NPC elections were certainly not the only exciting thing that happened at Convention. Over 1300 delegate members (and hundreds of alternates) also committed to expanding our socialist electoral program, building out our Palestinian solidarity and internationalist organizing work, deepening our participation in the labor movement and toward an arms embargo against Israel, fighting fascist attacks on immigrants and standing up against state repression from ICE, preparing for May Day 2028, building worker power against Amazon, uniting labor and the left to run a socialist for president in 2028, and so much more!

We were honored by a fiery keynote speech by Rep. Rashida Tlaib, who grounded us in our place in American history and exhorted us to “take this country back for our working families and defeat these pathetic, cowardly, hateful fascists. We’re going to win because we don’t have any other options, and yes, we are going to free Palestine. They don’t have any other choice. Our movement isn’t going anywhere, and we’re just getting started.” This was one of our most mediagenic conventions yet, with new media and streamers like Hasan Piker observing and engaging in real time, and mainstream outlets like The Guardian noting the energy of our winning streak and Rolling Stone going in-depth on how we are preparing to seize the political moment.

We also had dozens of volunteers helping staff and elected leadership with press, tech, security, and more, in a real show of collective organizing strength. And even members who did not attend were able to tune in for deliberation and to watch our first-ever Cross-Organizational Political Exchange with socialist parties from around the world and labor unions and social movement organizations from around the country — over 1400 unique viewers watched the Convention livestream online, averaging about 200 at any given time. You can read the preliminary results here, and we will be keeping you updated as the NPC considers the overflow items over the next few months.

There’s a real excitement that comes from charting a path forward, and now it’s time to knuckle down and get to work on putting these ideas into action. If you need a bit more inspiration, though, here are some things you can sign up for right now:

- Solidarity Dues Phonebank (Sunday 8/31 at 4pm ET/3pm CT/2pm MT/1pm PT): Member dues are DSA’s primary source of income and help create some of the amazing tools and resources that DSA offers. Help us call through folks and make the hard ask: can we count on you to switch to Solidarity Dues? It’s a friendly list of fellow DSA members, so these are fantastic folks to practice those organizing conversations with.

- Fight Fascism, Build Socialism (Tuesday 9/2 at 7pm ET/6pm CT/5pm MT/4pm PT): The chaos of this second Trump administration is an onslaught meant to overwhelm us and make us feel powerless. But we are not powerless when we’re organized, and we’re still fighting for someone we don’t know. Join us on this call featuring how DSA members across the country are fighting back! After Labor Day, it’s time to take the fascists back to school.

- YDSA’s Fall Drive Launch Call (Tuesday 9/2 at 8pm ET/7pm CT/6pm MT/5pm PT): At campuses all over the United States, YDSA chapters are continuing their fights for ambitious demands around sanctuary campuses, worker rights, divesting from the genocide in Palestine, and so much more! To kick off this semester, we’re gathering to hear from successful chapters around the country about what they’re working on, how they plan to grow this fall, and what you can do to see the same impact locally!

- September Leadership Intensive (Saturday 9/6 and Sunday 9/7 starting at 1pm ET/12pm CT/11am MT/10am PT): Ready to take the step into chapter or committee leadership? The Leadership Intensive is the most comprehensive training that DSA provides (it’s 2 days long!) for folks who are ready to take on leadership work, and will get you familiar with everything from tech tools to the theoretical basis of the democratic project.

- Emergency Tenant Organizing Committee 2025 Fall Training Series (Saturdays in September beginning Saturday 9/6 at 2pm ET/1pm CT/12pm MT/11am PT): The Housing Justice Commission’s summer Emergency Tenant Organizing Committee (ETOC) cohort is now accepting prospective tenant organizers. ETOC is an initiative to promote the formation of militant tenant unions through tenant-to-tenant training and instruction. In this series, you’ll learn the fundamentals of tenant organizing on a citywide or regional scale.

- National DSA 101 (Sunday 9/14 at 2pm ET/1pm CT/12pm MT/11am PT): Whether you’re just now becoming a member or you’re a longtime member interested in doing more DSA work, come to this program to get a birds-eye view of what we’re up to.

- Socialist Cash Takes Out Capitalist Trash Phonebanks (various times/dates): Help support our nationally-endorsed slate by spreading the good word about (and asking comrades for donations for) our candidates in Detroit, Jersey City, Atlanta, Renton, Tacoma, and Ithaca, all of whom are fighting like hell to win and build power at the municipal level.

And that just scratches the surface of upcoming opportunities! Keep an eye out for new opportunities — we’ll keep sending them your way.

In the meantime, solidarity to you and we can’t wait to see you at an event soon!

In struggle,

Megan Romer and Ashik Siddique

DSA National Co-Chairs

The post Your National Political Committee newsletter — Ideas into Action appeared first on Democratic Socialists of America (DSA).

Buffalo DSA Urges Reconsideration of Broadway-Fillmore Police Training Facility

Since March 2025, Buffalo DSA has endorsed LOLA’s Communities Not Cops campaign, with overwhelming support from our general membership. As this project begins to receive the citywide attention and debate it deserves, the Buffalo DSA Steering Committee reaffirms our support of efforts to educate and agitate against a police training facility and shooting range on Paderewski Drive. We also urge all members of Buffalo DSA to follow LOLA’s calls to action re: demanding Common Councilmembers vote “NO” on the rezoning of the Paderewski Drive location, as listed on their Instagram page.

The creation of a police training facility increases the Buffalo Police Department’s capacity for targeting working-class Buffalonians through violent interventions, especially those in minority ethnic groups and within our city’s poorest communities. This is especially heinous considering Paderewski Drive was once home to a community center; we are disappointed to see the city invest in more militarized policing, rather than restoring a public civic space. This is completely counter to the just city we deserve – not just for those in the immediate neighborhood, but for working class communities citywide. We have been disappointed by the limited scope of debate around this project to this point, which suggests that only the immediate neighborhood will be impacted by this facility. We encourage comrades and neighbors to consider the larger ramifications of a police training facility of this kind.

Said limited scope of debate stems from a source actively collaborating with the Buffalo Police Department to push this project through. The Central Terminal Neighborhood Association is claiming a mandate to speak for the entire area, despite reports that opposition to the project has now spread beyond LOLA’s initial campaign, and to Broadway-Fillmore community members who have just learned about the project relative to its progress. Neighbors deserve fair representation of the project to them, rather than vague promises of a “community benefits agreement” with BPD – the details of which include only surface-level commitments toward “youth programs” in part of the facility and keeping neighborhood trees intact. We also condemn undignified smear tactics, printed or otherwise recorded publicly, that concerned citizens across Buffalo are only seeking cameras or clicks.

As the Common Council, the Buffalo Police Department, and other crucial city officials collude to advance this project via their Sep. 2 vote, we once again doubt their belief in democratic processes, and question the Central Terminal Neighborhood Association’s mandate to speak for the city on the matter.

Our chapter’s vision for demilitarized policing takes from the rich history of American socialism, notably from the legacy of American socialist Eugene V. Debs. Debs stated in 1918, after his conviction for violating the Sedition Act:

“While there is a lower class, I am in it, while there is a criminal element, I am of it, and while there is a soul in prison, I am not free.”

While we cannot speak for a long-deceased comrade, Debs’ rhetoric throughout his life demanded the liberation of the working class from oppression and tyranny. To aid and abet the tyranny of modern policing is antithetical to the American socialist tradition.

Reflecting on the 2025 National Convention

We had an absolutely fantastic time with our comrades at the 2025 DSA National Convention! Many of our Steering Committee members were serving as delegates for their chapters so we were able to catch up in person – some of us meeting IRL for the first time!

And of course – we have news to share with you regarding the direction of DSA’s national electoral work as determined by Convention as well as updates from our Socialist Cash Takes Out Capitalist Trash fundraising project!

For the NEC, Convention kicked off with us hosting an electoral-themed social on Thursday night, where participants were invited to make buttons of their favorite nationally-endorsed DSA candidates and partook in a get-to-know-you BINGO as they mingled with our candidates and electeds. The activity prompted people to meet comrades from chapters running campaigns with national endorsement, socialize with people who serve on their chapter’s electoral working groups, and connect with comrades from a variety of chapter sizes. Participants received an NEC bucket hat!

Electoral Workshop Results

On Friday, we hosted an electoral workshop to an overflowing room of participants!

At the NEC workshop, we had attendees complete an Electoral Program Report Card where they graded their chapter’s programs according to a variety of pillars of our electoral work (endorsements, leadership development, SIO work, etc.). We got 96 responses, which provided the NEC with an unprecedented look into our chapters’ electoral programs across the country.

The Steering Committee is pouring over the responses and will share a summary of our findings once we complete it.

Missed the workshop and want to grade your own electoral program? Check out our slides and then fill out your report card.

We also had great conversations at our table – leading to 38 applications being submitted by DSA members wishing to join the NEC.

Electoral-Related Resolutions & Amendments Passed at Convention

This convention was a pivotal one for the future of our electoral work! Check out the following resolutions which will change the course of our electoral strategy both locally and nationally.

- NEC Consensus Resolution: This resolution sets a new course for our national and local electoral work, including running candidates on independent ballot lines, updating our national endorsement criteria, creating a national socialists in office network, and issuing best endorsement practices recommendations for locals.

- Towards Deliberative Federal Endorsements: This amendment to the consensus resolution updates our federal endorsement criteria, requiring Q&As with federal candidates and more deliberation prior to endorsement.

- Carnation Program Amendment to NEC Resolution: This amendment to the consensus resolution sets a goal of running 5 candidates for Congress in 2028 running on a platform of 5 priority issues, including ending U.S. militarism, Medicare for All, and more.

- Invest in Cadre Candidates and Political Independence: This amendment to the consensus resolution commits to prioritizing running more cadre candidates at the local level, expanding the NEC’s fundraising efforts, and increasing staff capacity to support NEC.

Next Steps

We’re very excited to begin implementing these mandates from convention, including our very own NEC Consensus Resolution. If you want to help out with this important work, please join the next all-member NEC call, or if you’re not a member apply to join the NEC!

Nationally-Endorsed Slate Fundraising at Convention

National Convention was the perfect opportunity to do some fundraising for our slate of candidates! Through the QR code at the table and promotion from Chanpreet during convention, we were able to get 104 donations during convention – 54 of which were first-time donors!

Since the start of convention, we have raised an additional $6,029.94 for our slate candidates (currently Denzel McCampbell, Jake Ephros, Joel Brooks, Kelsea Bond, and Willie Burnley Jr.) on top of the $61,659.32 we had already raised so far this year!

Thank you to everyone who attended the National Electoral Commission’s events!  We hope to see you at our upcoming all-member meeting so we can get to work on implementing the mandates from convention.

We hope to see you at our upcoming all-member meeting so we can get to work on implementing the mandates from convention.

Shout-out to Cleveland DSA and Snohomish County DSA for allowing us to borrow your button makers. And thank you to Nick W for your button production run prior to convention!

– Your National Electoral Commission Steering Committee

Bernie Sanders Endorsement of Rebecca Cooke A Betrayal of Socialist Movement

On August 23rd, Bernie Sanders will be hosting a “town hall” event with Rebecca Cooke, candidate in the 2026 Democratic Party 3rd Congressional District election, near Viroqua. This follows his June 19th endorsement of her. We, the Executive Committee of the Coulee Region chapter (CDSA) of the Democratic Socialists of America (DSA), denounce this endorsement and campaign event and urge Senator Sanders to withdraw this endorsement.

Senator Sanders has been a principled socialist for his entire life, and has been a leader and inspiration for millions of progressives and socialists for decades. This made his endorsement of Rebecca Cooke extremely shocking. Rebecca Cooke is no socialist, or even a progressive. She refuses to endorse Medicare For All. In 2024, she was “grateful” to be endorsed by the genocide-apologist organization Democratic Majority For Israel.1 In June of this year, she was a featured speaker at “WelcomeFest”, a convention of the anti-progressive wing of the Democratic Party, sharing the billing with genocide-apologists and neoliberals.2 In the struggle between progressives and reactionaries within the opposition to the current fascist regime, she has declared on which side she places herself- it’s not with us, and it shouldn’t be with Bernie Sanders.

There are two other candidates in this primary, namely Laura Benjamin and Emily Berge, who would make far more sense for Senator Sanders to endorse. Both have endorsed Medicare For All. Both have better stances on Palestine. Laura Benjamin is a member of DSA, is committed to socialist principles, and is a fiery public speaker. Emily Berge is firmly in the La Follette Progressive tradition and has years of experience in local elected office.

For these reasons, in the spirit of socialist comradeship, the Coulee Region chapter of Democratic Socialists Of America urges Bernie Sanders to withdraw his endorsement of Rebecca Cooke.

COULEE DSA EXECUTIVE COMMITTEE & CHIPPEWA VALLEY DSA OC, AUGUST 19th, 2025

Coulee Democratic Socialists Of America can be found at https://coulee.dsawi.org/, on Facebook, on Instagram, and by emailing couleedsa@gmail.com. Chippewa Valley DSA can be reached at chippewavalleydsa@gmail.com

1“DMFI PAC announces new endorsements in Arizona, New York, & Wisconsin” https://dmfipac.org/news-updates/press-release/dmfi-pac-announces-new-endorsements-in-arizona-new-york-wisconsin/

2“I Just Got Back From the Centrist Rally. It Was Weird as Hell.” https://www.thenation.com/article/politics/welcomefest-dispatch-centrism-abundance/

The post Bernie Sanders Endorsement of Rebecca Cooke A Betrayal of Socialist Movement first appeared on Coulee DSA.

Review: The Long Reroute, by David Duhalde

David Duhalde’s essay, “The Long Reroute: A Historical Comparison of the Debsian Socialist Party of America and the New Democratic Socialists of America,” places debates within today’s DSA in historical context while advocating for democratic decision making as the best means for resolving them. For those not familiar with the author, it’s useful to know a little bit about his background. David’s father survived Chilean fascism and imbued in him a profound faith in democratic socialism and the working class. He joined DSA in 2003, so he is just about the oldest of the new DSA. He’s held many responsible posts—from the bottom to the top and back again—in DSA over the last quarter century and is just as committed and involved today. That is a model of leadership to which all DSA cadre ought to aspire. And, as he makes clear in a footnote—always read the footnotes—he is a member of the Socialist Majority Caucus (SMC). I consider him an outstanding thinker and a good friend. I learned long ago that making friends with politicos in competing or complementary factions or organizations is one of the best ways to keep your balance under conditions not of our own choosing.

David’s essay is divided into four parts, starting with a sketch of Socialist Party history and the long metamorphosis of one part of it into today’s DSA, followed by three punchy sections comparing debates around labor, elections, and internal party organization in the SP and DSA. David admirably compresses 100 years of history into a few pages and I think his overview is an excellent primer for new DSA members. Rather than cutting ourselves off from all that messy history, David invites us to learn from it in order to fight more effectively today. And, to put it bluntly, to toughen up. Faction fights, splits and bad tempers are just as much a part of our history as are comradeship, faith, and unity.

If I’m being a critical critic, I think the first section could have been extended to focus on the causes and conflicts that led to the SPs rise and fall. For instance, David notes that the SP “steadily declined nationally in the 1920’s” after reaching 120,000 before World War I. But he doesn’t really offer us a convincing “why.” It’s a tough question and he wanted to get to his main points, but I’d like to know what he thinks. For comrades who want to know more about the contest between the SP and the CP in the 1920s and 1930s, I’d recommend perusing David’s comprehensive bibliography. If you’re interested in filling out the picture of post-WWII democratic socialism, read Chris Maisano’s A Precious Legacy in Socialist Forum. And if you buy me a beer, I’ll tell you more than you want to know about the “takeover attempt” by Trotskyists in the 1930s.

But those are minor preliminaries. The real strength of David’s piece follows in three sections dedicated to labor, elections, and internal party organization. I’ll comment on each and then conclude with a few summary remarks.

Labor

All socialists worth their salt have looked to the organized working class as the only force powerful enough to defeat the billionaire class. Exactly how to transform the proletariat from a class in itself to a class for itself (Marx’s old dictum) has been, and continues to be, easier said than done. David provides us with a useful crash course in U.S. labor history, from the Knights of Labor to the AFL to the IWW and the CIO and traces how competing strategies divided sections of the socialist movement. I think he’s right to highlight that today’s DSA, with the benefit of hindsight, has managed to coalesce around some of the most successful of these strategies, what we might call a flexible rank-and-file approach. As he notes, “While this strategy was not universally accepted when it was proposed in 2019—many veteran DSAers were uneasy with publicly siding in internal union disputes and elections—it has gained more widespread acceptance among different caucuses and factions of DSA over the last few years.” I don’t think it’s possible to overstate just how important this insight is and David is correct to draw attention to it. This ethos is not the property of one or another caucus, but represents the shared experience and intelligence of thousands of DSA members fighting to build durable labor unions.

Elections

David points out that the Debsian-era SP’s electoral strategy had sought political independence from the beginning. Electoral independence did not constitute a left v. right tension. Remember, the Democratic Party of this era was the party of the Klan in the South and Tammany Hall in the North. Debs and Berger both wanted an independent Socialist ballot line. There’s a lot more to say about what happened in the 1930s during the New Deal, but David concentrates on how a section of the SP—led by Michael Harrington in the Democratic Socialist Organizing Committee in the 1960s and 1970s—hit on the strategy of “realignment,” which aimed to transform the Democratic Party into a kind of social democratic party. The results were, generously, a mixed bag.

Today’s DSA has adopted, according to David, a new strategy, “contesting Democratic primaries as the main arena for struggle,” typically conceived of as preparing for a “dirty break”—or a “dirty stay,” as David has suggested elsewhere—with the Democrats. Just how and when and under what circumstances such a break might occur, has led to “serious tensions” inside DSA today. As he puts it, “unity around the mere idea of being or becoming a party does not necessarily result in consensus around how the party and its elected officials should operate, especially together.” Although David’s SMC caucus has a definite view on this question, here David raises a political conundrum that all of DSA will have to confront, namely, “the polarization today between the Democratic and Republican parties, which did not exist when the Socialist Party operated,” adding how such polarization “makes voters more partisan and less open to new options.” He concludes that “Democratic voters may be happy to vote for socialists within primaries, but may not want to vote for the same candidate if they ran on another line.” The road to any kind of break leads through demonstrating, in practice, how to overcome this dilemma.

Internal organization

This final section of David’s analysis contains—and it ought to—his most controversial assertions. Rather than shy away from the debate, or paper over disagreements, David makes a clear case for how he believes internal debates are most fruitfully resolved. I would characterize David’s view as a strong belief in the efficacy of conducting and resolving political debates within DSA’s structures, however imperfect they may be. There’s simply no other way to settle sharp disputes. At times, as has been common in the past, that turns out to be impossible and some comrades may decide to leave. For example, David summarizes the case of several debates around Palestine:

1. The factions and partners in the new DSA can change but the program such as Palestine solidarity will continue. 2. These disagreements are largely born out of internal, “homegrown” struggles over major strategic disagreements about how to approach politics. Both groupings who departed DSA were active in the organization as individual members, not as outsiders trying to influence DSA policy to foster splits. People leave when they feel they can no longer achieve their objectives through the existing democratic process.

Turning to factionalism, David argues there are two principle kinds: entryism and homegrown. In terms of entryism, I differ with his view—it’s overly generalized and defensive—but I’ll leave that discussion for another time. I will simply point out the danger that lumping together any future organizational merger with different political tendencies—whether they emerge from labor, civil rights, or other socialist movements—under the banner of “entryism” can be counterproductive. For instance, longtime—and now former—DSA member Maurice Isserman placed the “blame” for DSA’s forthright defense of Gaza on unnamed “entryists.”

More fruitful, in my view, is David’s description—drawing on his discussion with Bill Fletcher–of the new DSA as “an unplanned left-wing refoundation.” That is, “the idea that a stronger left is possible through both regroupment of existing radical structures into a new formation alongside the rethinking and retooling of current left-wing strategy into an alternative orientation.” Of course, there is a difference between an entryist smash and grab operation and honest regroupment, my only point is that comrades should be careful not to paint any organizational regroupment as necessarily entryism with a negative sign placed above the latter. David, I believe, provides the tools to do so by placing his matter-of-fact summaries of the many homegrown caucuses within DSA next to his observation that some of those caucuses have “external influences,” which is only natural and to be expected. In fact, those influences are a sign of DSA’s openness and vitality, not a weakness. As such, “factionalism” is just a normal consequence of any genuinely democratic organization, especially one that has grown as explosively as DSA. As David explains,

DSA’s factionalism is homegrown. Simply put, the divisions and debates originate largely within DSA, not outside of it. For the hundreds of members who were long-time members of other organizations before joining DSA, tens of thousands more had their first experience in a political organization, much less a socialist one, in DSA. These two groups do interact with each other and many of the caucuses have external influences—both contemporary and historic. Every grouping has their own unique history.

David is, I think, right to downplay generational conflict within DSA, although he does note that older and more experienced members can have difficulty adapting to new melodies and—to extend Irving Howe’s metaphor—new and younger members might not recognize the lyrics. My only quibble here is that David’s one example of intergenerational dynamics is the resignation of some long-term, high-profile members over DSA’s forthright defense of Gaza. That is certainly worth pointing out. But I would also point out that—to my understanding—the “old guard” welcomed the transformation of the organization in 2017. That decision to turn over the keys to the newbies represents an act of political perspicacity on the part of DSA’s veterans and, in my experience, is not as common as one might hope. Of course, David’s own middling generation, those who joined between 9/11 and Bernie 2016, represented a mediating layer of cadre who paved the way for mass growth by creating institutions such as Jacobin and revitalizing YDSA. It’s a lesson that the new generation of DSA cadre should take to heart as we prepare for larger influxes of new socialists and new phases in the ongoing “unplanned left-wing refoundation.”

Lastly, The Long Reroute fits squarely into an undervalued category of what I might call cadre writing. It is a form of exposition that draws on academic and specialist knowledge, but extracts political value expressly designed to speak to socialist organizers and leaders. The general public may get something out of it, although they may well be overwhelmed by all the history and acronyms. And academics may well dismiss it as lacking in original archival research, even as the best of them engage with it. It’s just what the doctor ordered for DSA’s developing cadre, that is, our most active and dedicated members who aspire to help lead DSA on both a national and local level. David’s work provides a framework and language for raising our cadre’s sophistication and capabilities and expands the possibility for caucus and non-caucus cadre to communicate and collaborate, even while debates rage on. It is a must read.

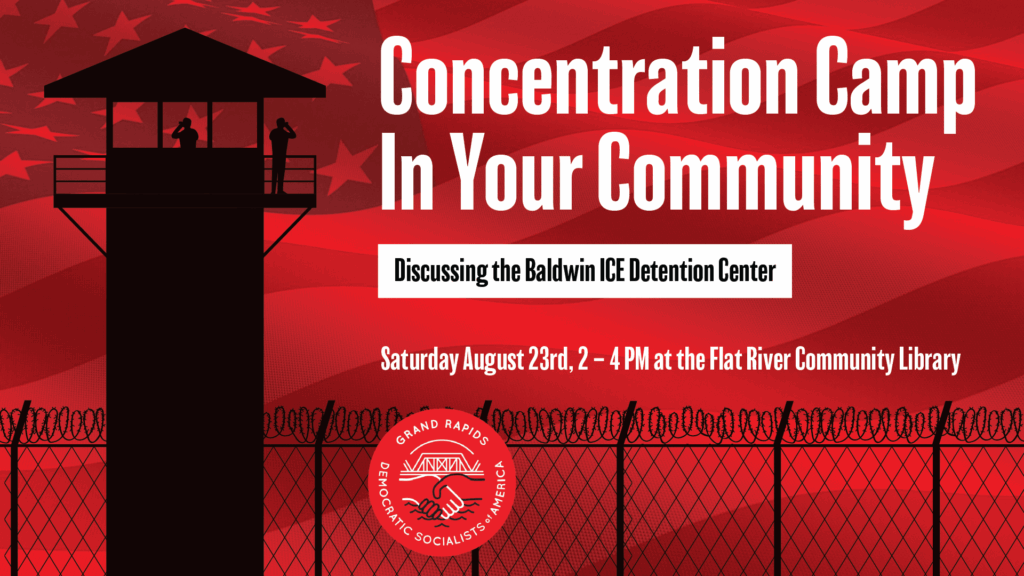

Concentration Camp in Your Community: Discussing the Baldwin ICE Detention Center with the GRDSA

We’ll be hosting our next Greenville event on Saturday, August 23rd, from 2-4 pm at the Flat River Community Library.

We’ll be discussing Trump’s new ICE Detention Center in Baldwin, Michigan. The conversation will center around the racist anti-immigrant efforts rising around us, why we’re against them, and what we can do about it!

RSVP to the event here, and share the details with a friend! We’re looking forward to a robust discussion with you.

The post Concentration Camp in Your Community: Discussing the Baldwin ICE Detention Center with the GRDSA appeared first on Grand Rapids Democratic Socialists of America.

Exert Your Right to Mask!

by Sam K.

Rights are not rights if we don’t use them, and we must use exercise them openly, frequently, and without reservation.

I don’t usually talk about masking very much, I just do it. I find people talk to me about masking more than I talk to them about it. The act of masking causes others to reflect; perhaps to feel some sort of guilt about themselves, or judgement about me and other maskers. This one time, let me make the case for masking for 2025 and the foreseeable future.

The techno-surveillance police state is already here – its gradually cemented itself in the digital and physical world we navigate our lives through. After 9/11, the normalization of surveillance has evolved from an initial public support for sacrificing freedoms for supposed “public safety,” to the shocking revelations of Edward Snowden’s whistleblowing, to an almost pathetic view of the security theater of going through TSA. Cameras are watching us in the sky – far enough away where we cannot seem them, but precise enough to see details on the ground. Many people tend to feel hopeless about avoiding such surveillance when thinking about this – but hope is not lost. The Electronic Frontier Foundation has been fighting for digital privacy rights for decades, paving the way for alternatives to Big Tech such as the Graphene OS android operating system, Proton emerging as a Google suite alternative, and the more widespread adoption of Signal. The use of these digital tools help to shield us from the surveillance state, but the digital privacy community and socialist organizers are failing to discuss how we can protect ourselves from both the surveillance state and fascist forces in public. Being tracked by the state or being doxxed and identified by fascist forces are real threats we must confront head-on.

Historically, bans on facial coverings have a mixed history in the United States. One the one hand, there were some 20th century laws passed in various states in efforts to crack down the Klu Klux Klan, while later being applied to Occupy Movements. On the other hand, In 1845, New York State passed an anti-mask law for “public safety” after a tenants’ revolt, known as the Anti-Rent War, or the Helderberg War. Many states, and the District of Columbia, either already have anti-mask laws on the books, have pushed for them recently, or likely will continue to push for them. While the legal statuses have been challenged and some have been struck down by the Supreme Court, we know these liberal institutions have already failed us, and will continue to enable fascism.

So, what happens when ICE starts going after socialists? Will you wear a mask to a protest or at court watching? What will you do when a police officer or a masked ICE agent claims you cannot wear a mask because you’re hiding your identity and you might be a terrorist? Will you comply, or will you disobey, whether legal or not? Will you start coughing, or will you verbally argue the necessity of masking to protect yourself from a contagious virus that can cause young, otherwise healthy people to become disabled and immuno-compromised? Actions speak louder than words.

I’ve now contracted covid-19 three times, the third leaving me with a compromised immune system and GI reactions to some of my favorite foods – which I had been eating during isolating and recovering from the third infection. Wearing good masks that fit your face absolutely works to protect yourself from covid-19, other viruses, and those brutal Austin allergies, too! Maybe you still don’t care about covid-19, and I don’t think I can convince you with words. But the reality is, you cannot mask only for protection from the fascist forces; you must also mask for your protection from airborne viruses. Otherwise, your masking would be atypical. It would signal a divergence in your regular behavior. Our safety and security practices are for all of the time. We always wear our seat belts, not just right before we get into a collision. Normalizing masking in 2025 and onward is a matter of practice, and just doing it. Do it at the grocery store, do it at your work place. Do it inside, and do it outside. Do it to protect yourself, and do it to remind others to do it – because actions speak louder than words. Exert your right to mask, and do it now – before its too late.

The post Exert Your Right to Mask! first appeared on Red Fault.

Democratic Socialism and the Automotive Industry

by Henry M.

A modern industrial society requires a democratically-controlled economy. Here is an outline of why that’s true

Few clearer exhibits of capitalism’s need for waste arrive in the mailbox than the annual Auto Issue of Consumer Reports. In it are listed and reviewed the multiple automobiles overfilling the categories (sedan, pickup, minivan, etc.) that have evolved since the Tin Lizzie went into production generations ago. (“435 Models Tested” in the 2024 edition.) The waste of labor and material involved in the manufacture of numerous candidates to fit each category, and the implications for democracy, are the subject of this brief diatribe, using the ubiquitous Sport-Utility Vehicle (SUV) as an example.

The SUV is a kind of mix of station wagon, minivan, sedan, and sports car. The general type really is useful, whether electric, hybrid or gasoline-burner. But so many of them!

courtesy of Hyundai Motor Group

courtesy of Martin Katler

courtesy of Hans Isaacson

courtesy of Maksym Tymchyk

Ten interchangeable models (with romantic names) just among the “Midsized 3-Row SUVs”! This overpopulation situation comes about because manufacturers want to maximize their profit, to fulfill the dreams of their managers and investors. This drive leads them to try to wrest away a portion of the market from one another. In this effort, they must differentiate their SUVs from those of their rivals. The cost in terms of finance they do not hide. But the hidden costs undercut democracy.

Bringing each SUV to reality and ultimately to the driveway of the buyer is not trivial. Each of the ten requires the fabrication of enormous metal-stamping molds for each body panel, of which there are a multitude on each different model. High-strength steel is fashioned into these giant molds, which must withstand the tremendous forces and the friction associated with crushing a big piece of sheet metal into the desired shape, requiring rare alloying elements.

Moreover, each mating mold pair, male and female, must be designed by skilled tool designers and fabricated by skilled toolmakers. And the body panels themselves: their shape emerges from the combined imaginations of Marketing and Industrial Design. Every swoop and curve, every seam, bulge and fin is wrestled over by trained professionals and reviewed by Management before the tooling is released for production…and they must all fit together perfectly, and not look quite like anyone else’s SUV. (A cursory inspection of a few SUV makes will reveal the differences among, for example, the front fenders.)

So thousands of labor-hours and refined talent are expended just on the body of each individual model…and that’s without looking at integration of the seats, the dashboard, the wipers, the door latches and the all-important cup holders. All these features, different for each, for every single, 3-row SUV, and we’ve ignored dozens of body categories (two-row SUVs, small sedans, etc.) Each of these models is dumped into the chaos and uncertainty of the marketplace; the makers must wait to see if their huge bets pay off in sales. Secrecy is crucial to profitability, an imperative of competition; none can afford to actually fabricate and test-market their creations among the public, as would be routine in a democratically-directed economy not dependent on secrecy. In the parts of our society permitted to operate along democratic principles, we discuss publicly and know in advance what policies will be adopted…not so when it comes to the operation of our enormous economy!

Now this is a critique of capitalism. So what’s to critique? Well, the flagrant waste. Among other things, the hoary Principle Of Interchangeable Parts is flung down and danced upon; standardization is spurned. If we as an electorate had dictated this state of affairs back in the Martin van Buren Administration and bequeathed it to our progeny for generations to come, it would be one thing. But that’s not how it happened. Over a century ago, when industrialization was young, people who had money to invest joined with others and built physical plants to manufacture cars. Others sought to compete with them. Millions went to work, of necessity, for the resulting corporations. Those manufacturers and their heirs have dominated our economy ever since. In requiring huge percentages of the population to engage in duplication of effort to earn a living, the economy misuses their labor.

But we are democrats. We believe ourselves capable of making the most important decisions in our society. Given the opportunity, we might not elect to make so many functionally interchangeable, but part-wise unique cars, each with its own infrastructure of parts and dealers. Socialism gives that opportunity.

Only socialism recognizes this silly duplication as a problem and proposes to correct it. Socialism, as a rationalizing force, would place direction and management of such an important part of our economy in the hands of the citizenry, for example through elected managers, like our choice of political candidates in conventional elections. All these manufacturers worked hard to provide us with things we don’t need, wasting resources, clean air and the labor of countless Americans. Socialism, somewhat more fundamentally than police and gender reforms, would impose order and planning, and democracy, on the productive capacities of our economy, and Consumer Reports would become thinner.

Respectable, proud democracy cannot coexist with this wasteful mode of industrial organization.

Henry M is an Automotive and Mechanical Engineer.

The post Democratic Socialism and the Automotive Industry first appeared on Red Fault.

Solar Bonds for our Communities!

Rooftop solar at Lyons Farm Elementary

By Aidan P and Carl H

Right now, people in Carrboro, Chapel Hill, Durham, and Hillsborough, as well as in Alamance and Chatham counties, are recovering from the severe and costly flash flooding brought on by Tropical Depression Chantal. We know that the climate crisis is making weather disasters more frequent and more intense, and our region is now threatened by supercharged floods, heat waves, and hurricanes. Even areas that were thought to be relatively safe are at risk. For example, North Carolina’s Appalachian Mountains, once seen as a refuge due to the cooler climate and inland location, were hit hard by Hurricane Helene in September 2024. Entire districts of Asheville were destroyed, tens of billions of dollars in damages were sustained, and many rural mountain communities were devastated.

But even though climate change is now a manifest reality, our leaders have utterly failed to meet the moment. At the federal level, investments and incentives for renewable energy are systematically rolled back, public lands are threatened, environmental regulations are aggressively slashed, and proper forecasting equipment and personnel are thrown to the wayside with deadly consequences. At the same time, big tech’s extremely dangerous and ecologically costly gamble on a mass buildout of deregulated nuclear plants to power AI datacenters continues to accelerate. State leadership is hardly any better. Duke Energy, with the help of politicians on both sides of the aisle, continues to drag its feet on cutting emissions, instead investing in new fossil gas infrastructure. Most recently, the state legislature overrode Governor Josh Stein’s veto and dropped North Carolina’s interim 2030 decarbonization goal, removing incentives for Duke Energy to shift to renewables and encouraging continued use of fossil gas. According to an analysis by NC State professor Joseph DeCarolis and his colleagues, this destructive bill will lead to a 40% increase in fossil gas generation in our state between 2030 and 2050. This is only the tip of the melting iceberg when it comes to Duke Energy’s disastrous activities, which also include greenwashing and mass deception, systematic subversion of democracy, and an allegedly cavalier attitude towards nuclear safety, among others.

Besides emitting greenhouse gases, burning fossil fuels also emits a huge quantity of toxic pollution harmful to natural ecosystems and human health, causing asthma, cancer, and heart disease. Furthermore, as anyone who lives near one of Duke Energy’s coal ash deposits knows, the ecological and human costs don’t end with emissions, also including the leaching of heavy metals linked to cancers, reproductive harm, and heart and thyroid diseases into soil and groundwater. In addition to the impacts on our communities and our health, the climate crisis compounds the more general ecological crisis as animals and plants struggle to adapt to a rapidly changing environment.

In contrast to burning fossil-fuels, solar panels convert sunlight directly into electricity, avoiding greenhouse gasses and other toxic emissions. Increasing solar electricity generation is an important step in the transition to renewable energy and a sustainable economy. The Triangle region receives abundant sunlight, an average of 4.5-5.4 hours of peak sun per day. Thanks to technological advances, solar panels today are efficient, long-lasting, and low-cost compared to other ways of producing electricity. Renewable energy sources like solar also stabilize energy prices, as they are not prone to the periodic severe price shocks experienced by volatile fossil gas markets.

While it is possible to fund solar installations through regular budget measures, this creates a false conflict between money for solar and money for other important public services. A bond resolves this, helping to facilitate the large scale solar projects necessary for a swift and comprehensive energy transition.

The solar bonds we are advocating would borrow money specifically to fund solar installations on public buildings like schools, libraries, public housing, and government buildings. Any renewable energy installations funded by these bonds should be publicly owned, and money saved that previously went towards paying Duke Energy's high electricity rates should, after paying off the bond, instead be allocated to improving public services or helping to raise the wages of sanitation workers, teachers, support staff, and other low-wage public sector workers.

These bonds are also a climate resilience measure. The importance of a climate resilient grid cannot be underestimated: this can be a matter of life and death during a climate disaster. For example, when combined with infrastructure hardening and the development of localized microgrids, the solarization of public buildings can ensure that our most critical public facilities stay on during the power outages that often accompany weather emergencies.

Depending on the specific needs of each county or city in the Triangle, these bonds could also fund other critical resilience, renewable energy, and energy efficiency measures. For example, a broader bond referendum could be used to fund efficient HVAC systems for our schools, improve stormwater infrastructure for our towns and cities, or even acquire property for new public housing. We encourage anyone familiar with the needs of their community to contact us and share what similar measures they would like to see included in local bonds.

Many cities and counties in North Carolina and across the South have already passed bonds to fund sustainability measures, including solar installations on public buildings. In 2020, Buncombe county, the city of Asheville, and Asheville’s Isaac Dickson Elementary School agreed to collectively spend $11.5 million on solar facilities capable of generating seven megawatts of power, mostly for public buildings -- schools, community colleges, community centers, and fire stations, among others. The majority of this money ($10.3 million) came from a bond issued by Buncombe county, approved unanimously by Buncombe county commissioners. Even Republican county commissioners voted to approve the bond, citing the cost savings, which more than covered each year’s bond payment. A 2024 initiative in San Antonio, Texas, provides a second example. Here, a total of $30.8 million was raised ($18.3 million from bonds, $10 million from Inflation Reduction Act tax credits, and $2.5 million from the State Energy Conservation Office), partially to solarize a variety of municipal facilities, such as municipal building rooftops and parking lots. San Antonio expects to pay off all debt within 10 years using savings accrued through the project, which also makes substantial progress towards the city’s goal of net-zero emissions by 2050. Locally, a 2022 Durham County schools bond included funding to solarize Lyons Farm Elementary School, which now supplies about 20% of its electricity from rooftop solar.

While we encourage local governments to adopt renewable energy measures through their regular budget proceedings, as Democratic Socialists we wanted to bring the issue directly to voters -- giving regular people a real say in important and economically consequential decisions brings us a step closer to the democratically organized economy we ultimately envision.

Currently, our goal is to get solar bonds on the ballot for Orange, Durham and Wake Counties, as well as for our smaller municipalities (Carrboro and Chapel Hill) and our larger cities (Durham and Raleigh) But make no mistake -- a solar bond is only the beginning. Powerful forces stand in the way of the comprehensive energy and sustainability transition our society needs, especially in North Carolina. To overcome these forces we need to build a mass movement that centers the multiracial working class and all the oppressed and colonized peoples of this land. One of the core goals of the mass movement must be to establish an energy system owned and planned by and for the people, an energy system that puts our interests and our planet over corporate profit. We invite you to join us.

Interested in helping? Triangle DSA’s Solar Bond Campaign Committee meets every other Tuesday at 6:00pm online, and is open to the general public. The committee has already reached out to potential coalition partners, and plans to build support through tabling and canvassing campaigns. The committee is also in the process of meeting with elected leaders to advocate for the bond. You can reach out to us directly to join in this important effort by contacting nctdsa.solarbond@gmail.com, or you can simply show up to a committee meeting!