The Suppressed History of the Black Socialist Tradition

Milwaukee DSA, allies support ICE Out plan for Milwaukee

The Milwaukee Democratic Socialists of America (DSA) and their allies are telling the Milwaukee Common Council to pass the ICE Out legislation package.

Announced earlier this month at City Hall, the package includes several pieces that will work to limit ICE operations in Milwaukee and help protect people here from the death, abuse, and chaos brought on by ICE during their operations across the country:

- Resolution declaring opposition to how federal immigration enforcement activities are occurring in the United States and amending the City of Milwaukee’s legislative package

- Communication from various City agencies relating to strategies and responses the City might use in response to militaristic actions undertaken by the federal government targeted at the City

- Resolution prohibiting the use of City property by federal law enforcement agencies engaged in immigration-related activities

- Resolution instructing the Milwaukee Police Department to protect the rights of community members when they engage in constitutionally protected speech and assembly, and intervene to protect community members if anyone, including other law enforcement agency personnel, attempts to abridge the public’s constitutional rights

- Ordinance prohibiting all law enforcement officers, when acting in an official capacity, from wearing masks or face coverings, and requires that both agency and individualized identification be worn

- Motion modifying Milwaukee Police Department Standard Operating Procedure 340 – Uniforms / Equipment / Appearance

- Motion modifying Milwaukee Police Department Standard Operating Procedures regarding the duty to intervene, investigate, and report unreasonable uses of force

- Motion modifying Milwaukee Police Department Standard Operating Procedure 172 – Sick and Injured Persons

- Ordinance creating an office for new Milwaukeeans

“Let this legislative package serve as a message that Milwaukee will step up against ICE and the authoritarian Trump administration ripping families apart,” Milwaukee DSA Co-Chair Autumn Pickett said. “I’m so proud to see that—after less than a day—nearly 4,000 emails have already been sent to City Hall, as everyday people join the call for these protective measures.”

DSA organizers are calling on members, supporters, and allies to email Milwaukee City Hall and tell the Common Council to pass this package quickly and do its part to keep Milwaukee safe from ICE.

“Our work doesn’t end here: More than 20,000 Milwaukeeans have already joined the local community defense network to watch for ICE activity, deliver groceries to at-risk families, inform our neighbors of their rights, organize within our unions to protect our workplaces, and so much more,” Pickett said. “We will continue to fight for the better future that all working people deserve.”

Milwaukee DSA is Milwaukee’s largest socialist organization fighting against imperialism for a democratic economy, a just society, and a sustainable environment. Join today at dsausa.org/join.

Weekly Roundup: February 24, 2026

Events & Actions

Tuesday, February 24 (6:30 PM – 7:30 PM): Ecosocialist Bi-Weekly Meeting (zoom and in person at 1916 McAllister St)

Tuesday, February 24 (6:30 PM – 7:30 PM): Ecosocialist Bi-Weekly Meeting (zoom and in person at 1916 McAllister St)

Wednesday, February 25 (12:00 PM – 1:00 PM): Rally for Net Zero and No Environment Dept Cuts (in person at San Francisco City Hall, 1 Dr Carlton B Goodlett Pl)

Wednesday, February 25 (12:00 PM – 1:00 PM): Rally for Net Zero and No Environment Dept Cuts (in person at San Francisco City Hall, 1 Dr Carlton B Goodlett Pl)

Wednesday, February 25 (1:00 PM – 2:00 PM): Sheriff Miyamoto: No Collaboration with ICE Terror (Sponsored by Free SF Coalition) (in person at San Francisco City Hall)

Wednesday, February 25 (1:00 PM – 2:00 PM): Sheriff Miyamoto: No Collaboration with ICE Terror (Sponsored by Free SF Coalition) (in person at San Francisco City Hall)

Wednesday, February 25 (6:45 PM – 8:30 PM): Tenant Organizing Working Group Meeting (zoom and in person at 438 Haight St)

Wednesday, February 25 (6:45 PM – 8:30 PM): Tenant Organizing Working Group Meeting (zoom and in person at 438 Haight St)

Thursday, February 26 (6:00 PM – 7:00 PM):

Thursday, February 26 (6:00 PM – 7:00 PM):  Education Board Open Meeting (zoom)

Education Board Open Meeting (zoom)

Thursday, February 26 (7:00 PM – 9:00 PM):

Thursday, February 26 (7:00 PM – 9:00 PM):  ICE Out Orientation (zoom and in person at 1916 McAllister St)

ICE Out Orientation (zoom and in person at 1916 McAllister St)

Friday, February 27 (9:30 AM – 10:30 AM):

Friday, February 27 (9:30 AM – 10:30 AM):  District 1 Coffee with Comrades (in person at Breck’s, 2 Clement St)

District 1 Coffee with Comrades (in person at Breck’s, 2 Clement St)

Friday, February 27 (7:00 PM – 9:00 PM):

Friday, February 27 (7:00 PM – 9:00 PM):  Maker Friday with PSAI (in person at 1916 McAllister St)

Maker Friday with PSAI (in person at 1916 McAllister St)

Saturday, February 28 (11:00 AM – 2:00 PM):

Saturday, February 28 (11:00 AM – 2:00 PM):  ETOC Session 4 – From Organizing Committee to Mass Organization (1916 McAllister St)

ETOC Session 4 – From Organizing Committee to Mass Organization (1916 McAllister St)

Saturday, February 28 (1:00 PM – 4:00 PM):

Saturday, February 28 (1:00 PM – 4:00 PM):  DSA SF at Alemany Farm (Alemany Farm, 700 Alemany Blvd)

DSA SF at Alemany Farm (Alemany Farm, 700 Alemany Blvd)

Sunday, March 1 (11:00 AM – 1:00 PM):

Sunday, March 1 (11:00 AM – 1:00 PM):  Sip ‘n’ Stitch (Coffee To The People, 1206 Masonic Ave)

Sip ‘n’ Stitch (Coffee To The People, 1206 Masonic Ave)

Sunday, March 1 (2:00 PM – 3:30 PM):

Sunday, March 1 (2:00 PM – 3:30 PM):  What Is DSA? (Ortega Branch Library, 3223 Ortega St)

What Is DSA? (Ortega Branch Library, 3223 Ortega St)

Sunday, March 1 (4:00 PM – 6:00 PM):

Sunday, March 1 (4:00 PM – 6:00 PM):  From Silence To Solidarity: Standing With The Iranian People (1916 McAllister St)

From Silence To Solidarity: Standing With The Iranian People (1916 McAllister St)

Monday, March 2 (6:30 PM – 7:30 PM):

Monday, March 2 (6:30 PM – 7:30 PM):  DSA Run Club (in person at McClaren Lodge)

DSA Run Club (in person at McClaren Lodge)

Monday, March 2 (6:30 PM – 8:00 PM): Homelessness Working Group Regular Meeting (zoom and in person at 1916 McAllister St)

Monday, March 2 (6:30 PM – 8:00 PM): Homelessness Working Group Regular Meeting (zoom and in person at 1916 McAllister St)

Monday, March 2 (7:00 PM – 8:00 PM): Labor Board – Flex Meeting (zoom)

Monday, March 2 (7:00 PM – 8:00 PM): Labor Board – Flex Meeting (zoom)

Tuesday, March 3 (5:30 PM – 7:00 PM): Social Housing Meeting

Tuesday, March 3 (5:30 PM – 7:00 PM): Social Housing Meeting  (zoom and in person at 1916 McAllister St)

(zoom and in person at 1916 McAllister St)

Tuesday, March 3 (7:00 PM – 8:00 PM):

Tuesday, March 3 (7:00 PM – 8:00 PM):  Public Transit Meeting (zoom and in person at 1916 McAllister St)

Public Transit Meeting (zoom and in person at 1916 McAllister St)

Thursday, March 5 (6:00 PM – 7:00 PM):

Thursday, March 5 (6:00 PM – 7:00 PM):  Social Committee (zoom)

Social Committee (zoom)

Thursday, March 5 (6:30 PM – 7:30 PM): Public Bank Project Meeting (zoom)

Thursday, March 5 (6:30 PM – 7:30 PM): Public Bank Project Meeting (zoom)

Thursday, March 5 (7:00 PM – 8:00 PM): Immigrant Justice regular meeting (zoom and in person at 1916 McAllister St)

Thursday, March 5 (7:00 PM – 8:00 PM): Immigrant Justice regular meeting (zoom and in person at 1916 McAllister St)

Saturday, March 7 (10:00 AM – 2:00 PM):

Saturday, March 7 (10:00 AM – 2:00 PM):  No Appetite for Apartheid Training and Outreach (in person at Arab Resource & Organizing Center (AROC), 522 Valencia St)

No Appetite for Apartheid Training and Outreach (in person at Arab Resource & Organizing Center (AROC), 522 Valencia St)

Saturday, March 7 (11:30 AM – 2:00 PM):

Saturday, March 7 (11:30 AM – 2:00 PM):  Organizing Mindset Training (in person at 1916 McAllister St)

Organizing Mindset Training (in person at 1916 McAllister St)

Sunday, March 8 (11:00 AM – 1:00 PM):

Sunday, March 8 (11:00 AM – 1:00 PM):  Physical Education + Self Defense Training (in person at Kelly Cullen Community, 220 Golden Gate Ave)

Physical Education + Self Defense Training (in person at Kelly Cullen Community, 220 Golden Gate Ave)

Sunday, March 8 (5:00 PM – 6:00 PM):

Sunday, March 8 (5:00 PM – 6:00 PM):  Tenderloin Healing Circle Working Group (zoom)

Tenderloin Healing Circle Working Group (zoom)

Monday, March 9 (6:00 PM – 8:00 PM):

Monday, March 9 (6:00 PM – 8:00 PM):  Tenderloin Healing Circle (in person at Kelly Cullen Community, 220 Golden Gate Ave)

Tenderloin Healing Circle (in person at Kelly Cullen Community, 220 Golden Gate Ave)

Monday, March 9 (7:00 PM – 8:00 PM): Labor Board – New Union Organizing (zoom and in person at 1916 McAllister St)

Monday, March 9 (7:00 PM – 8:00 PM): Labor Board – New Union Organizing (zoom and in person at 1916 McAllister St)

Check out https://dsasf.org/events for more events and updates.

Phone Zap to Support the Oakland People’s Arms Embargo

Join the cross-Bay phone zap to demand an end to weapons shipments out of OAK! We need Oakland Mayor Barbara Lee to sign on to this campaign – call to urge her to support the Oakland People’s Arms Embargo. We are flooding the phone lines this Monday (yesterday!) through Wednesday, February 23rd – 25th from 9:00 AM – 5:00 PM. CALL EVERY DAY! Script HERE.

Calling Out Capitalism: An Op-Ed Writing Workshop, Part 1

TONIGHT! Join Ed Board for Part 1 of our Op-Ed Writing Workshops. We’ll cover techniques and strategies for writing effective op-eds, and lead some writing activities to get you crafting op-eds of your own. Starts tonight, Tuesday February 24th at 6:00 PM at 1916 McAllister.

Part Two, featuring peer feedback on your op-ed drafts, is up in March. Stay tuned for details!

ICE Out of SF: Plug in and Strategize!

We’ll be strategizing, and connecting the various initiatives happening across the city.

This is a great event for people already involved in immigrant protection to expand their work, as well as for folks looking to get plugged in.

Some of the initiative we’ll discuss are: Adopt-A-Corner, Court watch, Accompaniment, Know Your Rights canvassing, and more!

Join us at 1916 McAllister St on Thursday, February 26 at 7:00 PM. RSVP here

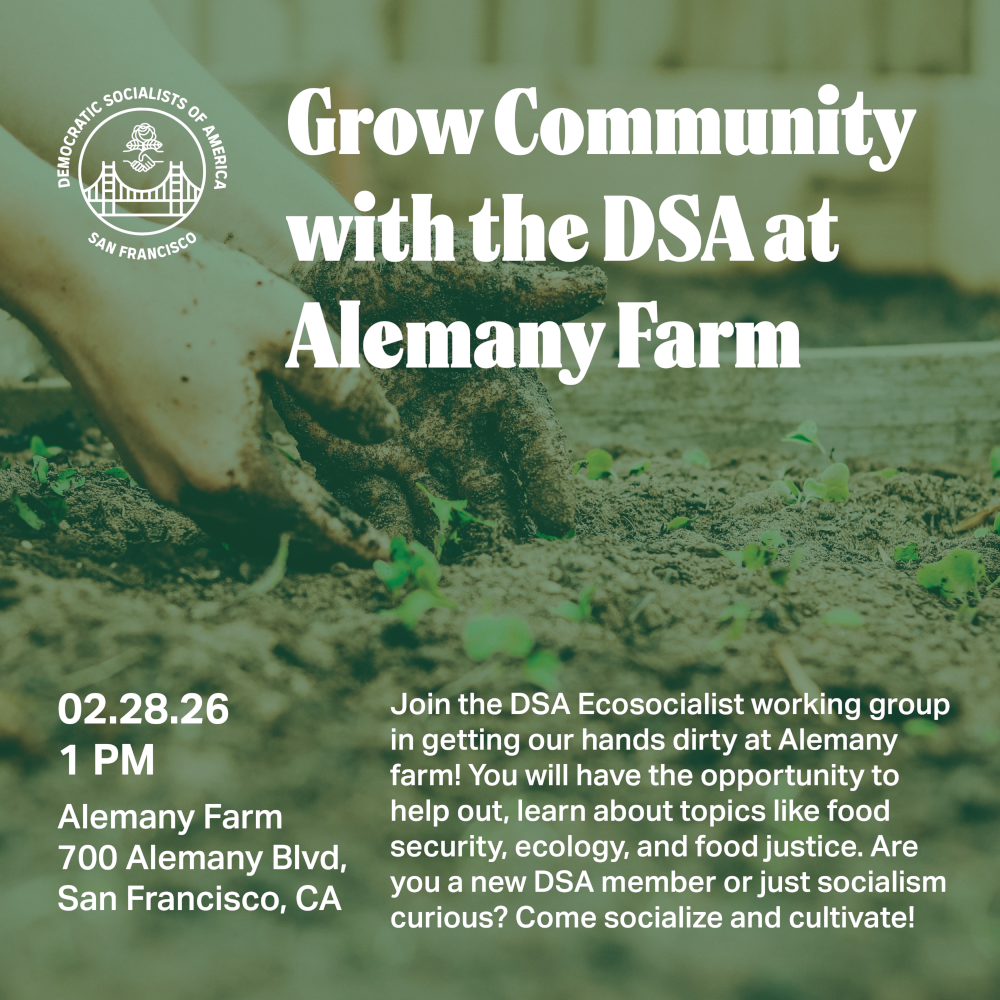

Grow Community with the DSA at Alemany Farm

Come join DSA SF’s Ecosocialist working group on Saturday, February 28th at 1:00 PM at one of San Francisco’s community gems, Alemany Farm.

This is a great event for both new members and long-time DSA members. Come expand your ecological consciousness and spend an afternoon with knowledgeable urban agriculturalists and fellow comrades. Email ecosocialist@dsasf.org with any questions. RSVP here

Maker Friday: PSAI Edition

Come make with us on Friday, February 27th from 7:00 PM – 9:00 PM at our office 1916 McAllister as we make zines, buttons, and brainstorm a logo together for the PSAI working group! No experience necessary. Please feel free to bring your own craft to work on as well  Masks will be required and provided.

Masks will be required and provided.

Emergency Tenant Organizing Committee (ETOC) Fundamentals of Tenant Organizing Watch Party

Looking to deepen your understanding of housing work on the ground? Interested in building durable tenant power in SF? Come learn how to organize tenant associations, fight landlords collectively, and build toward radical tenant unionism in San Francisco. The last ETOC watch party is this Saturday, February 28th, at 11 AM at our office (1916 McAllister), focusing on turning socialist analysis into mass tenant struggle: investigation, campaigns, and building real tenant organizations that can win. If you’re serious about anti-landlord work, this is where to plug in.

Sip and Stitch

Enjoy yarn arts or other crafting? Come craft with comrades! On Sunday, March 1st, 11:00 AM – 1:00 PM at Coffee to the People, 1206 Masonic Ave, we’ll be knitting, crocheting, needlepointing, and more! Bring your current project or come learn something new!

From Silence To Solidarity: Standing With The Iranian People

From Silence To Solidarity: Standing With The Iranian People

Iran has been in the news a lot lately. Protestors have taken to the streets to demand social and political change. The government has responded by killing and injuring thousands of protestors, conducting mass arrests, and shutting down the internet and telecommunications. In the meantime, the US has used these developments as a pretext to carry out a dangerous and illegal imperialist escalation against the regime. While these developments are recent, they build off of several threads–on the one hand, a long history of US imperialist intervention in Iran from the overthrow of Mossadegh to the dollar imperialism we see today; on the other, several decades of resistance and struggles by the Iranian people for political and economic change.

As leftists, how do we make sense of all this? Join DSA SF as we discuss Iran’s history, Iranians’ current realities, and the role that the Iranian left has played in standing up to US imperialism and to the current regime. As we take on this complex but critical conversation, we aim to break free of the false, harmful dichotomy of supporting imperialist designs for regime change on the one hand and viewing Iran’s regime uncritically on the other. Together we can work to build a socialist anti-imperialist understanding of the Iranian people’s resistance and right to self-determination.

Join us at 1916 McAllister St on Sunday, March 1 at 4:00 PM – 6:00 PM. RSVP here.

State of Play: Electoral Strategy in Los Angeles (Part 2 of 2)

In Part I we described the mainstream political landscape of Los Angeles, the large scale and the major constituencies of the single-party Status Quo Coalition: a wing of wealthy corporate and business Democrats in an uneasy coalition with multiracial liberal democracy blocs of non-profits, labor organizations, and ethnic interest groups. Since publication, another dramatic series of events has shaken up the 2026 Mayoral race in Los Angeles. Center-left Austin Beutner is out of the race following the death of his daughter, while a shocking last-minute announcement from Councilmember Nithya Raman has introduced a new set of challenges for Los Angeles’s DSA chapter to reckon with, sparking hot debate within the membership about the nature of the chapter’s relationship with endorsed Socialists in Office (SIOs). The media comparisons to Zohran Mamdani have only intensified, but the differences between both the candidates and their local political contexts remain stark enough for LA Times columnist Gustavo Arellano to take note.

To help make sense of the moment, we will describe how DSA-LA’s endorsements have evolved in response to the local factors sketched in Part I, and how our victories have in turn begun to reshape that political landscape. DSA’s 2025 National Convention resolutions defined an ideal-but-not-exclusive candidate archetype: the “cadre candidate.” We include some evaluation of our endorsees’ relationships with the LA chapter, as this concept looms large in the post-Zohran DSA environment and colors many chapter activists’ perspective on endorsements. We start with a brief history of the chapter’s electoral endorsements since 2020.

The New York Post’s new West Coast outlet does its thing.

2020

Nithya Raman was modern DSA-LA’s first endorsement for LA City Council, running a 2020 campaign that centered on the city’s wasteful and cruel approach to homeless sweeps and opposing the power of organized landlords. For Los Angeles, Raman was a transformational candidate, the first to unseat an incumbent in a generation.

Far from a core or “cadre” member, Raman only joined DSA in the leadup to her campaign, and has never been an organizer within the chapter’s ranks. Rather, she joined DSA after co-founding the SELAH Neighborhood Homelessness Coalition. At the time, DSA-LA was organizing across renters and unhoused tenants and against the inhumane policies of the city through campaigns like Street Watch LA and Services not Sweeps. Raman’s campaign was backed by the Services Not Sweeps Coalition that included both DSA-LA and SELAH. Though the vote was contested, her campaign received endorsement from DSA-LA and National DSA, and the chapter ran a robust member campaign in support – but notably, never represented a majority or even a plurality of her grassroots volunteer campaign.

Councilmember Raman’s relationship with DSA-LA, and indeed the broader Angeleno grassroots left, has been strained. At the time of her victory, Raman had made no explicit commitment to ongoing engagement (often referred to as co-governance) with DSA-LA — and no Socialists in Office program yet existed within the chapter to enable such ongoing engagement. Though Raman was consistent in her support for renter protections and a humane homelessness policy, she still shies away from adopting the “democratic socialist” label, and her relationship with the chapter almost broke in 2024 when membership approved a censure over accepting an endorsement from a small pro-Israel Democratic club during her hard-fought reelection campaign.

Regardless of these tensions, the impact of her win on the electoral landscape in Los Angeles is undeniable. Despite the entirety of the Status Quo Coalition (including late interventions by Hillary Clinton and Nancy Pelosi) supporting her opponent, Raman’s election began to hint at the electoral influence of the new DSA core constituency: young, multiracial, low and middle-income renters dissatisfied with the city’s neoliberal status quo. That such a constituency could organize and seriously disrupt the city’s comfy electoral order set off alarms among LA’s established powers.

Data analysis by Tal L

2022

The impact of the new democratic socialist constituency roared into full force when two new DSA-endorsed candidates, directly inspired and endorsed by Raman, defeated incumbents from LA’s multiracial liberal democracy blocs.

In 2022, Eunisses Hernandez unseated former Latino-labor stalwart incumbent Gil Cedillo in Council District 1, a rapidly-gentrifying district containing Highland Park, a neighborhood friendly to socialist candidates. Cedillo’s history as a labor leader with SEIU and a champion for undocumented immigrants in the State Assembly had established him firmly on the labor edge of the Status Quo Coalition. His city council tenure demonstrated clearly the compromises and contradictions of his Latino liberal bloc – its flexibility to become an early endorser of Bernie Sanders in 2016 while simultaneously embracing support from real estate and business interests.

Hernandez was also decidedly not DSA cadre, joining the chapter during the endorsement process and with a background in anti-carceral political advocacy, the founder and former director of abolitionist nonprofit La Defensa. In office, she has been among the most outspoken members of the socialist bloc, and has organized in office extensively with the chapter in her district.

Hugo Soto-Martinez, representing Los Angeles’ socialist hotbed neighborhoods in Echo Park and Silver Lake, is the clearest LA example of a cadre candidate. From 2018 until his campaign launch, he organized within DSA-LA in the chapter’s NOlympics campaign, and then its Central Branch as a pandemic-era neighborhood organizer. Council District 13 office staff are active DSA-LA members in the central branch, and a burgeoning district committee is taking shape in CD13 to enable mass engagement among constituents. Importantly, Hugo was politicized in and maintains his primary political home in Los Angeles’ labor movement, particularly UNITE HERE Local 11, a fixture of LA’s powerful immigrant-led service and hospitality union sector with a long history of involvement in municipal politics.

The elections of Soto-Martinez and Hernandez coincided with the LA Fed Tapes leak and signaled a shift in the Status Quo Coalition. Soto-Martinez’s deep labor connections allowed him to win endorsements from a significant portion of Los Angeles’ strongly-incumbent-preferring labor federation. Hernandez’s ties to the broad anti-carceral and abolitionist nonprofit world solidified opposition to police funding as a core value of the newly forming political bloc, which has been repeatedly outvoted on questions to expand LAPD. DSA-LA’s non-electoral campaigns in support of workers, immigrants, and renters are increasingly co-organized with LA’s unions, while organized socialists grow in number and organization among some of labor’s rank and file. Los Angeles’ status quo coalition has begun to slowly reshape itself: DSA and the progressive edge of Los Angeles labor and justice-based nonprofit worlds are coming into connection, and police, landlord, and commercial interests are cleaving in reaction. It remains to be seen how durable or consistently ideological this realignment and its associated movement connections are.

Former LA Federation of Labor president Ron Herrera caught on tape.

2024

By the end of 2023, DSA-LA had to confront the limits of organizing a candidate as loosely aligned as Nithya Raman. Both a censure and revoking her endorsement were put to a chapter vote, with 60% of votes cast approving the censure, and 40% in favor of revoking the endorsement altogether. The endorsement stood, the chapter mobilized a field campaign, and Raman squeaked out a 50% win in the primary round, avoiding a runoff against LA Police Protective League and landlord backed challenger Ethan Weaver.

Additional endorsements in this cycle focused on spurring growth in the chapter’s San Fernando valley branch: longtime chapter member Konstantine Anthony, who cruised to victory as an incumbent on Burbank city council, and the unsuccessful runs at Burbank and LA council seats for Mike Van Gorder and Jillian Burgos.

2024’s general election added Ysabel Jurado to the city council bloc, a tenant attorney who replaced disgraced labor figure Kevin de León. Jurado, who spent two years as an organizer with DSA-LA’s Power Mass Transit campaign leading into her campaign for office, notably received the support of the LA Fed. It was a startling turnaround for de León, who was previously a poster child for the Eastside ethnically Latino Labor-supported Status Quo Coalition. But mainstream Democrats all the way up to Joe Biden had called on Kevin de León to step down in the wake of the leak; de León responded by not only remaining in his seat, but seeking reelection. The optics of the moment were surely clear to the Fed, and Jurado became the first DSA-LA member in the modern era to secure their powerful endorsement.

A 2024 election mailer paid for by Kevin de León.

The four-person bloc of Socialists in Office has achieved policy wins, most recently leading the way for city council to respond to years of organized pressure by the Keep LA Housed coalition. Tenants in rent-stabilized housing have won significant relief from exorbitant rent increases for the first time in 40 years, as well as codified anti-harassment provisions. A focus on services over sweeping encampments has shown promise in lowering the horrific rate of unsheltered homelessness in the city, though the scale of the problem remains overwhelming, and the economic outlook under Trump increasingly bleak. Major labor-backed initiatives to increase wages for tourism workers were passed over fierce opposition from LA’s tourism industry. The socialist bloc can often win alignment from progressive council members, but sometimes functions as a distinct minority that takes dissenting or protest votes, particularly regarding police funding.

This alone is a departure from norms in city government. Since at least the early 2000s in the wake of Los Angeles’ last charter reform, Los Angeles City Council established an ever-growing culture of consensus, under which items were only brought to a vote once they had overwhelming support. Under Council President Herb Wesson prior to Nithya Raman being seated, council consistently held a 99.9% unanimous vote rate. Though these habits are beginning to break, the expectations of “executive consensus” among LA’s “mini-mayors” remains a source of conflict between movements and their candidates.

2026

In the 2026 endorsement cycle, new candidates resemble the mix of longtime DSA organizers and movement allies that characterize NYC-DSA’s endorsed candidates. Challenging Los Angeles’ most conservative incumbent in Council District 11, Faizah Malik is public policy attorney for progressive policy shop Public Counsel, and like Raman and Hernandez, joined DSA-LA as a part of her preparation to run for office.

Estuardo Mazariegos, running against termed-out councilmember Curren Price’s hand-picked successor in Los Angeles’ most impoverished District 9, is a director in the community organizing, base-building NGO Alliance of Californians for Community Empowerment (ACCE). A member since mid-2020, he served for a time as a coordinator for DSA-LA’s South Central-Inglewood branch. These two candidates were both leaders on behalf of their employers in the successful Los Angeles rent stabilization campaign alongside DSA-LA, building trust and goodwill.

Marissa Roy, our endorsed candidate for city attorney, may have the tightest links with the chapter: a member since 2021, she strengthened her organizing skills through leadership in electoral working groups, while also being a regular participant in DSA’s political decision-making. Roy is also involved in various non-socialist political organizations around Los Angeles – most notably the Working Families Party (WFP), but also including the circuit of Democratic Party clubs and progressive Democrat-affiliated political organizations like the California Women’s List. On the strength of her legal career, which kicked off with campaigns to end worker misclassification and wage theft in the Port of Los Angeles, Roy has secured endorsement from the LA Fed, as has Faizah Malik.

DSA-LA’s slate of endorsed candidates: Dr. Rocio Rivas for School Board District 2, Estuardo Mazariegos for CD9, Faizah Malik for CD11, Eunisses Hernandez for CD1, Hugo Soto-Martinez for CD13, and Marissa Roy for City Attorney.

If the increasing willingness of Los Angeles Labor to support democratic socialist candidates for municipal office heralds a realignment of LA’s historic powers further towards a politics of class— of tenants and workers against landlords and bosses— this realignment is ongoing and incomplete, with Estuardo Mazariegos splitting labor support in his race with two other challengers. It has also triggered a backlash. Los Angeles’ business associations, typified by the anti-DSA PAC “Thrive LA”, has singled out Eunisses Hernandez as their top target this cycle, while drafting another business challenger to Hugo Soto-Martinez, forcing DSA to split our resources in defending multiple candidates. But in response, labor at large is backing a massive independent expenditure to support the re-election of Eunisses Hernandez as well as the insurgent Faizah campaign.

A left-labor political pole

To date, conditions in Los Angeles have incentivized a focus on LA city council rather than state legislative seats. The imperative to win those seats has primarily surfaced candidates who sit at the intersections of DSA with other elements of Los Angeles’ existing movement and progressive networks. The significant power of LA’s council seats has allowed DSA-backed council offices to win major policy victories, while also complicating messaging as movement and candidates try to build shared inside-outside tactics and strategies, with all the contradictions that effort entails. These victories have brought DSA-LA increasingly into alignment with the left wing of organized labor and Los Angeles’ robust nonprofit sector, aiming to sow the seeds of a left-labor political pole mobilized against Los Angeles’ committed capitalist interests.

Of course, winning a campaign is only the very beginning for a socialist in office— everything changes when an upstart “outsider” begins to experience the pressures of the “inside”. This has profound implications for organizers, as winning powerful positions with outsider candidates cannot be decoupled from the practice of political coordination, democratic decision-making, and an empowered chapter membership actively engaged in the institutions of civil society. Our core belief is not in any given candidate, but in the transformative power of a democratic socialist organization – one that emphasizes a deep commitment to the twin goals of member political education and member democracy.

In our next piece, we will do a closer examination of key players and electoral strategies among DSA and the Angeleno left, as well as the challenges facing DSA-LA as the organization navigates governance and mass organizing in the newly-forming left-labor political landscape.

Economic Inequality Means Income and Wealth: Why We Endorsed Both “Tax the Rich” Ballot Measures for November

Bernie Sanders came to Los Angeles to rally for the Billionaires Tax.

After a special zoom meeting on February 1 to hear arguments pro and con, California DSA State Council delegates voted unanimously to support “The Fair and Responsible Tax Plan for California’s Wealthy”. This statewide campaign embraces two ballot measure efforts: the Education and Healthcare Protection Act of 2026, and the Billionaires Tax, both of which are currently circulating petitions for signatures to place the measures on the November ballot. California DSA will now run a combined campaign to tax the state’s wealthy—both on their income and on their wealth, in order to fund schools and services.

Everyone’s heard of the billionaires tax. It’s been all over the mainstream press, mostly in the form of billionaires sobbing that if it passes they will have to leave their beloved California. Bernie Sanders recently came out to Los Angeles to rally on behalf of the measure. The tax would assess the state’s two hundred billionaires 5% of their hoard, er, wealth, and give them five years to pay up.

Below the radar

Mostly flying below the radar so far is the other progressive tax: the Education and Healthcare Protection Act of 2026. This tax already exists, originally as Prop 30 in 2012 and renewed in 2016 as Prop 55. But it’s a temporary tax and expires in 2030. This year’s measure aims to make it permanent.

Which is important. It brings in around $10 billion each year for schools and services – so far well over $100B over the last dozen years. It taxes the top two percent of California income earners—in other words, it doesn’t affect anyone reading this article; and on the slim chance that it does, I’m sure you know you can afford to pay it without any pain ($361K and above for single filers, $721K and up for joint filers).

The two measures do different things. The Billionaires wealth tax is meant to fill the hole of federal Medi-Cal cuts coming our way thanks to the fascist Trump regime’s Big Ugly Bill.

The Education and Healthcare Protection Act income tax supports all services in California. K-12 and community colleges together get 40% of the revenue with the rest split among higher ed, health care, transportation and other social services.

Prop 55 is a pure progressive tax; only the richest two percent of Californians pay it. It needs renewal because if it sunsets in 2030 the public sector will lose tens of thousands of jobs and have to slash services for millions of people, and the richest taxpayers, already way too rich for their own good, will get an unneeded multibillion dollar tax cut.

The Millionaires Tax campaign of 2011-2012 was a rowdy grassroots movement that forced Governor Brown to merge his ballot measure with theirs to create Proposition 30.

Historic achievement

Let me pause for a minute to celebrate what a historic achievement it was to pass this in the first place. Prior to 2012 it was common political wisdom in the golden state that a progressive tax couldn’t be passed. Why?

Prop 13, one of the key early signals of neoliberal austerity, got passed in 1978 by a two to one margin and for decades afterward was considered the untouchable so-called “third rail of California politics”. It was sold to voters as a solution, in a time of high inflation and quickly rising property taxes, to the problem of keeping Grandma in her home on her fixed income. It sharply limited residential property tax increases and put a raft of other restrictions on the state’s ability to raise revenue. Prior to Prop 13 California always ranked in the top ten states in per student funding. Post-Prop 13 we were more often in the bottom ten.

The campaign for it was a racist dog whistle, pointing a finger at lazy welfare cheaters—that is poor people of color—who received the hard-earned property tax dollars of virtuous homeowners—that is, middle class white people. Most people voting for it did not understand that its provisions also applied to commercial property; large corporations like Chevron and Disney made out like bandits, essentially stealing billions of dollars every year from schools and services to line the pockets of their shareholders instead.

Largely due to Prop 13, and until 2012, California was therefore understood to be an “anti-tax state”. We* changed all that with Props 30 and 55, which demonstrated that actually, some taxes, e.g., taxing the rich, were quite popular.

Millionaires Tax campaign leaders, 2012: (from left to right) Amy Schur of ACCE; Rick Jacobs, Courage Campaign; Joshua Pechthalt, CFT; Anthony Thigpenn, California Calls; and pollster.

It is important to mention that we had to overcome the initial opposition of Governor Jerry Brown, who proposed a mix of progressive and regressive taxes to fill the massive state budget hole created by the Great Recession in 2012. The California Federation of Teachers and its Reclaim California’s Future coalition (California Calls, ACCE, and Courage Campaign) asked him to join forces on a straight-ahead millionaires income tax. For months he refused, trashing us in public and peeling the unions in our coalition away by telling them if they didn’t drop us and come over to him, he wouldn’t sign any legislation they supported.

We call this “blackmail”, and it worked for a while; CFT became the only union aboard our campaign. But together with our community coalition partners we built a rowdy grassroots movement in the streets. We had clear, simple and persuasive messaging — “Tax the rich for schools and services” and beat his measure in five straight opinion polls. Our campaign culminated with a march of ten thousand outside his Capitol window, every other marcher holding a “Millionaires Tax” sign. For good measure, just to put a point on it, we occupied the Capitol rotunda for six hours.

So then he sued for peace. Brown came to CFT president Josh Pechthalt’s house to negotiate the deal (and in the process help Pechthalt’s daughter with her math homework). The compromise measure, which became Prop 30, actually raised more money than our Millionaires Tax would have. But the Millionaires Tax was going to be permanent, and Brown insisted on a five-year temporary tax. He wanted to add a one-cent sales tax increase, which we opposed and negotiated down to a one quarter of one cent increase. We also negotiated a shorter four-year term of the sales tax, and a longer seven-year term for the progressive income tax.

With the other unions back in a reunited coalition, Prop 30 sailed to victory against major opposition spending; and with this 2012 win we set up Prop 55 in 2016, when we eliminated the sales tax piece (which only raised an eighth of the revenue), making Prop 55 a pure progressive tax, and extended it to the year 2030.

That’s four years away. Why do it now, you might ask? Now we get into the politics behind these two measures, and why California DSA has a rare opportunity to lead by example in the Golden State’s progressive political realm.

The temporary Proposition 30, passed in 2012, was renewed as Prop 55 in 2016, and needs to be made permanent.

Coalition politics

The Education and Healthcare Act of 2026 is the product of the labor/community progressive tax coalition that emerged from Prop 30. This coalition has gone by different names over the fifteen years of its existence, but involves the same core group behind Props 30 and 55, and a 2020 effort, Prop 15, to raise taxes on big commercial property. Many California DSA members worked on the latter campaign. In the end we lost that one 52-48. Had it not been for the pandemic, which prevented us from running a field campaign, no one doubts we would have won. It would have brought in an estimated additional $10 – 12 billion to state service revenues each year, and reformed an important piece of Prop 13.

UHW, the lead organization of the current Billionaires tax, did not succeed in its consultation with the progressive tax coalition before launching. It is at this point unclear whether the two ballot measure groups will do what is obviously needed, which is coordinate the campaigns so that at the very least they don’t get in each other’s way. And better, combine their efforts and messaging so that voters understand why we need two progressive taxes addressing overlapping but separate issues.

UHW belongs to the SEIU State Council. That’s the largest single-union federation in California. SEIU State Council and the California Teachers Association (CTA) are the two big dogs in union politics in California. When they work together they are a real counterweight to big business. Right now CTA and the California Federation of Teachers (CFT) are backing the effort to make Prop 55 permanent and not backing the billionaires tax.

You would think that since it belongs to the SEIU council, UHW would have secured its endorsement. But SEIU State Council will not make a decision about the billionaires tax until it qualifies for the ballot, which won’t be known until May. Why does UHW lack the support of its own state council? Because, as with the progressive tax coalition, UHW did not have a successful conversation with its council before going ahead with its campaign.

There are now a couple more unions on board the billionaires tax—UNITE HERE Local 11 in LA (which supports both taxes) and California Teamsters Council. Along with California DSA and the Bay Area’s Federal Unionists Network hub, that will help. But this is not a sizeable coalition as of yet. It’s not clear one will emerge—not because the cause isn’t worthy, or because the tax isn’t desperately needed, which it is, but because UHW hasn’t persuaded other organizations to come aboard—especially with the group that knows best how to do this. The UHW potentially upset the applecart of the coalition’s longterm strategy, which was to first make sure that we solidified the Prop 55 revenue stream and then go after an additional progressive tax in 2028.

There are of course no guarantees that either measure is going to pass. Given the animus toward the ultrarich right now, and increasing public awareness of economic inequality and the connections between billionaires and fascism at the federal level, both measures should make it. But the insane current wealth of the billionaire class means they could dump five hundred million dollars against the two measures to forestall paying future taxes totaling much more than that. They have already been putting together tens of millions in opposition spending. If the two campaigns are not united in message and tactics billionaire opposition could prove deadly.

California DSA can lead by example

It doesn’t have to be that way. California DSA has a great opportunity here to lead by example. If we create a good set of messages that work for both campaigns and collect signatures and canvass and create earned media for both, we can show the two groups the importance of a united campaign. We should be under no illusion that we can directly influence the campaign decision-making tables where the price of a seat is a lot higher than we democratic socialists can afford. But by cooperating with both groups and showing that we can bridge the siloes in the labor movement, we can simultaneously advance these necessary progressive tax measures and the democratic socialist cause in California.

The Education and Health Care Protection Act proposes to make Prop 55 a permanent tax on the top two percent of California income earners.

How you can help

By now you’re wondering, “What can I do to help?” Glad you asked. There are two things you can do right away.

One: get petitions and collect signatures. We will have a one-stop shop soon for both petitions. But in the interim, you will have to get them from two places. Click here to fill in a form and get sent petitions for the Billionaires Tax. Click here to fill in a form and get sent petition for the Education and Health Care Act.

Never collected signatures before? You’d be surprised how easy it is. Start with your own household; call on your friends and neighbors; circulate among co-workers. If you get ambitious, go out to a mall or set up a table with a student or faculty organization at a college.

Two: Click here to download a template resolution for your DSA chapter to endorse the joint campaign. Follow your local chapter bylaws regarding submission of such resolutions and adjust the template as necessary. Our campaign for the two taxes will be much more powerful as our chapters officially come on board.

As the lopsided economic inequality in California is exacerbated by the Trump administration’s federal funding cuts, the multiracial working class will need these two revenue streams to keep the state—already one of the most expensive places to live in the nation—livable. Time to get to work.

*I was communications director for the CFT at the time.

East Bay Starting to Move Toward May Day

The panel of labor and community leaders, from left to right: Steven Pitts, moderator; Theresa Rutherford, SEIU 1021; Francisco Ortiz, United Teachers of Richmond; Grace Martinez, ACCE; and MT Snyder, FUN.

It was a dark and stormy night. Which caused some anxiety among the half dozen or so East Bay DSA organizers on Tuesday evening, February 10. They were concerned that their work over the previous couple months to build the “May Day in the Time of Trump” event might be dampened by a reduced turnout.

They needn’t have worried. Perhaps it was the promise in the publicity of “light supper will be served” that offset the threat of rain. But more likely the motivation for the 130 or so people who showed up came from anticipation they would receive some clear information about the state of the movement against Trump and MAGA in the East Bay, and what they might expect in the near future. In that they were not disappointed.

Push the conversation forward

According to the organizers, their goal was to help push the conversation among unions and progressive community organizations a step or two forward toward large May Day demonstrations in the Bay Area this year. They also hoped that the coalition of organizations co-hosting the event (Alameda Labor Council, SEIU 1021, ACCE, Bay Resistance, the Federal Unionists Network and several union locals) would reach out to their members and bring a diverse mix of folks to the meeting. Beyond that, they wanted the evening to help spread understanding that a previously missing factor in the growing movement against American fascism had dramatically appeared on January 23 in Minneapolis: revival of the general strike as an available tactic in the contemporary class struggle.

Alameda Labor Council leader Keith Brown opened the program with greetings to the audience and remarks on the inspiration provided by the people of Minnesota in their life and death struggle with ICE kidnappings and murders. He then introduced labor historian and filmmaker Fred Glass, who provided background on some of the key features of May Day history, including its long association with immigrant rights, red scares, general strikes, and the struggle for the eight-hour workday.

A crowd of 130 came out in the rain in downtown Oakland to hear about progress toward making May Day 2026 a memorable one and a stepping stone to May Day 2028.

After screening his 30-minute documentary, We Mean to Make Things Over: A History of May Day, Glass took a few questions from the crowd before turning things over to a panel of labor and community leaders. These included Theresa Rutherford, president of SEIU 1021; Francisco Ortiz, president of United Teachers of Richmond; Grace Martinez, Associate Director of the Alliance of Californians for Community Empowerment (ACCE); and MT Snyder, a Bay Area leader of the Federal Unionists Network (FUN). Retired UC Berkeley Labor Center associate chair Steven Pitts moderated, deftly putting the panel through its paces.

Pitts had his panelists address three questions: What did they think about the current state of preparedness of the East Bay community in building a movement to fight fascism, oligarchy and the billionaires and—most immediately—taking on ICE, should it arrive Minneapolis-style in force on our turf? What was their organization doing to prepare for mass action by May Day 2028? And how did they view the possibility of this year’s May Day as a steppingstone toward 2028?

Rutherford described the many fronts on which her local—largest in the Bay Area—operated. She underscored the challenges in coordinating the sprawling jurisdictions of the union, and pledged to work together to build the unity necessary for successfully pushing back against Trumpian fascism.

Ortiz recounted the patient steps taken by his union over the past few years as it built to running a successful four-day strike late last year, which resulted in an 8% salary increase, smaller class sizes, and protections for teachers on H-1B visas, among other negotiations issues. The West Contra Costa School District administration hadn’t agreed to any of these proposals before the strike. Ortiz noted the union’s consultation with parents prior to and during bargaining to ensure community support, and emphasized that the bargaining and strike occurred along the lines of a “bargaining for the common good” approach. Which, as in the Twin Cities, is an important part of building connections to do things like thwart ICE incursions.

Martinez spoke on behalf of ACCE and Bay Resistance, on whose board she represents ACCE. She recalled the organizing that went into the People Over Billionaires march in Pacific Heights in November, and told the audience about the community mutual aid efforts tracking ICE and building neighborhood relationships in which her groups were involved. She observed that in these coalitions labor, the partner with the most resources, didn’t always listen as well to the other partners as they might, and expressed the hope that that would change as we move forward.

Waking up

MT Snyder said that federal workers unions have been more or less asleep for decades, and the destruction raining down on government services and jobs in Trump’s second term has been a wakeup call. She reviewed the formation of FUN and noted the central role played by the rank and file in reaching across the unions’ boundaries to assert the need for common defense and begin to tie them together in action. She urged members of the audience involved in political work to talk and organize with the FUN members employed in federal agencies aligned with that work (e.g., climate justice and the Environmental Protection Agency).

Spirited group discussion, directed by Labor Notes staffer Keith Brower Brown, followed the panel presentations and revealed a wide range of political activities and experience, from a neighborhood Indivisible group formed by older women who had never been involved in politics before to veteran organizers enthusiastic about the rising possibilities for mass action.

According to the sign in sheets, just one fifth of the audience were DSA members, fulfilling the hope of the event organizers that the chapter wouldn’t simply be speaking with itself.

California Red readers interested in learning the history of May Day can view We Mean to Make Things Over. It can be found on the California Federation of Teachers’ website here, available to stream for free.

2025 California Red News Quiz Winners

Congratulations to our prize winners! First prize goes to Maya P, who achieved a perfect score of ten out of ten, choosing the correct answer and citing the California Red news article that the information came from. Second place winner: Ronan C. Third place: Christopher K. Questions and answers are displayed below.

1. Which County Board of Supervisors became the first in the country to adopt an Ethical Investment Policy (EIP) prohibiting investment in companies with ties to the Gazan genocide after being pushed by a BDS effort in which DSA was involved?

Alameda County!! "PALESTINE ORGANIZERS WIN: Divestment from Israel Becomes Policy for

2. What chapter was praised by the Central Labor Council for its work to help pass Measure A, a local tax supporting health care in the November 2025 election?

Silicon Valley "Silicon Valley DSA Helps Pass Measure A (Along With Prop 50)"

3. An organizing committee (pre-DSA chapter) was one of many DSA entities around the country working to bar low budget Avelo Airlines from local airports for its contract with the federal government to transport ICE detainees. Where is this organizing committee located?

Humboldt County/Eureka "Toxify the Brand: How a Mass Movement is Punishing a Deportation Airline"

4. Identify three indications of rising fascism in the United States since the inauguration of Donald Trump in January.

Trump's pardons of the January 6 insurrectionists; Persecution of immigrants/deployment of the National Guard/increased ICE raids; Arrest of political opponents (a judge, union leader, mayor, and senator) "This Dumpster Fire of a Reichstag Fire"

5. Identify three anti-fascist actions taken by DSA chapters in California since the inauguration of Donald Trump in January.

Two-day community picket outside the ISAP office in San Francisco to prevent mass arrests of immigrants (East Bay) "California DSA Chapters Swell the Ranks of 'No Kings Day'"; Organizing with local and national community groups to fight back against ICE and the National Guard takeover of Los Angeles in June (Los Angeles) "DSA-LA Organizes to Fight Fascism with Democratic Socialism"; Passing Measure A to fund the Santa Clara County Health System (Silicon Valley) "Silicon Valley DSA Helps Pass Measure A (Along With Prop 50)"

6. What does the ongoing resurrection of Native Californian ceremonies from past erasure have to say about the struggle for socialism today?

Ceremonies hold us together and remind us of who we are, especially as a collective. Reclamation of joy is resistance. Banding together and choosing to love each other in the struggle for freedom is necessary if we are going to win against fascism. "How to Survive Horrible Things Part 3: Ceremonial Freedoms"

7. Who was the figure from California's socialist history whose story contained similar elements to Zohran Mamdani's but whose campaign ended with defeat?

Job Harriman "What California Labor History Has to Say About the New York Mayor’s Race"

8. What was the name of an anti-capitalist event in which the event coalition brought together people, amphibians and mollusks?

People Over Billionaires march "People vs. Billionaires in San Francisco"

9. What is FUN, and what chapter has been campaigning alongside it?

Federal Unionists Network, East Bay "East Bay DSA Joins With Federal Unionists to Fight Trump’s Attacks"

10. What was your favorite California Red article in 2025?

PALESTINE ORGANIZERS WIN: Divestment from Israel Becomes Policy for Alameda County

Six Reasons Why I Choose ROC DSA

by Miriam J

Time is money, in a literal sense. I have chosen to sink a lot of my time and labor into ROC DSA, and I have lately been asking myself why. I think this is a good and healthy thing to ask.

At this time, I have what we in the therapist biz call a “dual relationship” with the chapter: it’s where I do my political organizing, the work that actually means something to me; the majority of my social life is connected to it; I have been elected to Steering Committee, meaning I have personally and ideologically tied myself to it. For all this, I want to be certain I’m putting my eggs in the right basket.

Thankfully, upon consideration, I continue to choose to be a part of ROC DSA. Further, I think our organization (specifically the Rochester chapter; I don’t make any claims about DSA nationwide) should be the banner under which local leftists and activists should unite. Here are my reasons.

1: Acknowledgment of Material Factors

This is no surprise for an explicitly socialist org, but it’s important. We don’t oppose capitalism because it’s vaguely evil or immoral. We oppose it because it deprives, it traumatizes, it kills human beings. Food, housing, clothing, our very planet, go to waste because it lines capital’s pockets. We point out that this is a system working as intended, and that that fact is abhorrent.

2: Democratic Structure and Accountability

“Our democratic processes” has been my go-to answer for what makes ROC DSA special for a while, but it bears further interrogation. It’s great that we operate in a truly democratic way, one which highlights that the United States is in no meaningful way a democracy by embodying an alternative.

Beyond that, I think that we do the same for accountability. This is a concept that, in my view, has been sullied by call-out culture and witch hunts within activist and marginalized spaces. Accountability is not a weapon against bad actors. It’s a way we mutually uplift and protect each other, even from our own mistakes. I believe these things are both parallel and inextricably linked; I’m not sure one can exist without the other.

3: Multiculturalism

Here’s another term that deserves elaboration, because I see a lot of corporate and institutional claims to it that are obviously false, but pervasive enough that they have shifted the meaning. When I say that we are multiculturalist, I mean that we try not to hold any element of the (white supremacist, patriarchal, imperialist) status quo as sacred. There is no reason to assume we know best, and doing so is dangerous at best.

Maybe that’s an unconventional definition; I’m sure there’s a better term I can’t think of for what I mean. But at the very least, I think this mindset is required for real multiculturalism to exist. Anyway, this is one a lot of activist/leftist groups fail at. For example, queer spaces I’ve been a part of tend to be eager to reject misogyny and homophobia, at least in their purest forms, but Christian-derived morality tends to remain under the surface. Certain kinks or beliefs are still unacceptable, even if they don’t tangibly affect anyone without consent. Men are still seen as inherently sinful and lustful. I’m glad that here, at least, we can call this kind of dogma into question, even when it comes from socialist origins.

4: Praxis

Praxis is the combination of theory and action. We can’t call ourselves real socialists, real activists, if we are ivory tower theorists, full of ideas and judgments for others, but without putting boots on the ground. This seems self-evident to everyone I’ve encountered in face-to-face activism; online discourse is another matter.

But what seems to be rarer is something we excel at, and to be honest, I think we get undue flak for sometimes. We are a political org. We refuse to hide or downplay that fact. We have conversations about and flexibility for what those politics are, beyond the umbrella term of “socialist,” but it’s at our core and informs our direct action.

5: Replaceable Leadership/Member Development

After making Steering Committee in a contested election after less than a year in the chapter, I’m living testament to this. Before I had an iota of faith in myself to run, I took minutes for Queer SG, I ran the occasional meeting, I sat in on a meeting of last year’s Steering Committee just to observe and listen. When I had questions about ROC DSA’s inner workings, they were not only answered, but praised.

I firmly believe I’m not uniquely “smart,” or a “natural leader.” I don’t even think those things exist. I was raised as a white male whose thoughts were put on a pedestal, so I love learning, thinking, and voicing my thoughts. I’ve also had the privilege not to spend all my waking hours working or caregiving, so I’ve had time to invest in learning. I say this not out of guilt, but because if I can hold a leadership position, any of us can. I love that our leaders are expected to take steps to make every member see that.

6: Aversion to Bad Gatekeeping

I’m of two minds about gatekeeping as a concept. On the one hand, I’m unsure it’s ever a good thing. On the other, no one is keeping gates closed to people like Joe Morelle or Donald Trump, at any point in their lives, and maybe they should. Either way, it’s obvious that it can be a harmful practice, individually and systemically. It also takes many forms: expectations of academic training, neurotypical-approved social behavior, fashion sense, and so on. None of these things are inherently good or valuable. As proponents of the working class, we should reject many of them. While we have a ways to go on this in our chapter, I think we’re still doing better than a lot of other spaces.

I don’t believe ROC DSA is perfect. We do a lot better at some of the above points than others. But these are values I see reflected in the chapter, its members and its work. I restate them here to say I think these are the most important things about our org. We should strive to embody them. These are the reasons I would rather enmesh myself with ROC DSA than any other group or project, and am proud to do so, and to bring others on board.

The post Six Reasons Why I Choose ROC DSA first appeared on Rochester Red Star.

How to spot unfair labor practices with the TRIPS method

Is your boss interfering with your organizing efforts? How can you know for sure? Check against this list of TRIPS tips.

The post How to spot unfair labor practices with the TRIPS method appeared first on EWOC.

Trump Doesn’t Always Chicken Out

Trump can follow through on his worst instincts — when it doesn’t threaten the interests of capital.

The post Trump Doesn’t Always Chicken Out appeared first on Democratic Left.