Central Indiana DSA

posted at

Dumped: How Charter Schools Cook Their Books, Choose Their Populations, and Profit

A zine covering how charter schools cook their books, choose their populations and profit.

Central Indiana DSA

posted at

Names and Numbers: Concerning Pro-Charter Advocates, Donors and Connections

A zine concerning pro-charter advocates, donors and connections

Central Indiana DSA

posted at

The Charter Industry: A Culture of Corruption and Exploitation

A zine on the culture of corruption and exploitation in the charter school industry.

Central Indiana DSA

posted at

¡Conozca Sus Derechos!

Una revista independiente del CASA sobre sus derechos.

Detroit Democratic Socialists of America

posted at

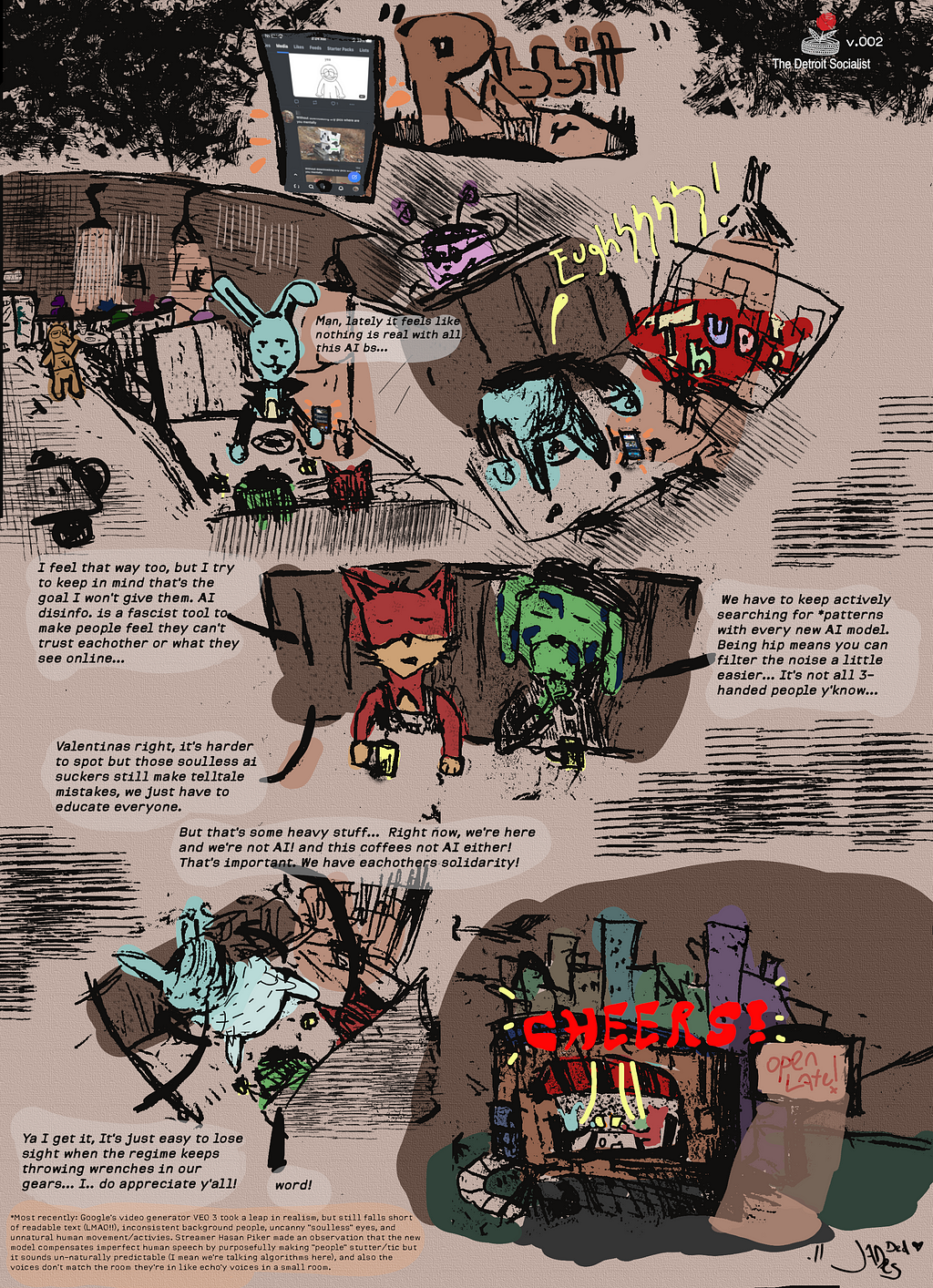

Rabbit Hole v.002

By: Jade DeSloover

Rabbit Hole v.002 was originally published in The Detroit Socialist on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.

Connecticut DSA

posted at

On The Value of Research

On April 1st, 2024, I received notification that a project for which I was a research assistant had been completely defunded. I was fired, and the future of the project remained uncertain. Our funding came from the Center for Connecticut Education Research Collaboration (CCERC) which was established from federal COVID relief funds to address pressing issues in Connecticut’s public schools and provide jobs to Connecticut researchers. Usually, I’d console myself and try to find hope for the future, but it was hard to feel that there was a future for researchers like me, who think people deserve better. Despite this hopelessness, I joined the DSA Education Justice working group: a coalition of educators, librarians, students, parents, and more that seeks to improve public education from a socialist lens. There is power and strength in the unity this working group provides. I found consolation with others who reassured me that they still see the value in research.

Connecticut DSA

posted at

Connecticut DSA

posted at

Red Catholic: A Life of Contradictions

My origin story feels like I am a contradiction in terms. Communist and Catholic—really? Looking back, my journey to communism is not one I ever imagined.

Growing up in the comfortable white settler community of East Lansing, Michigan, I certainly was not exposed to oppression.